Chaining up microbes prevents ‘bacterial sex’ and provides new way to control spread of antibiotic resistance, says new study.

During typical infections, pathogenic bacteria are in such low concentrations that they rarely encounter one another. It would be like accidentally bumping into people you know at a music festival.

Dr Douglas Brumley

A new study has shown for the first time exactly how a vaccination instructing the body to produce the intestinal antibody – known as secretory IgA – can protect against disease.

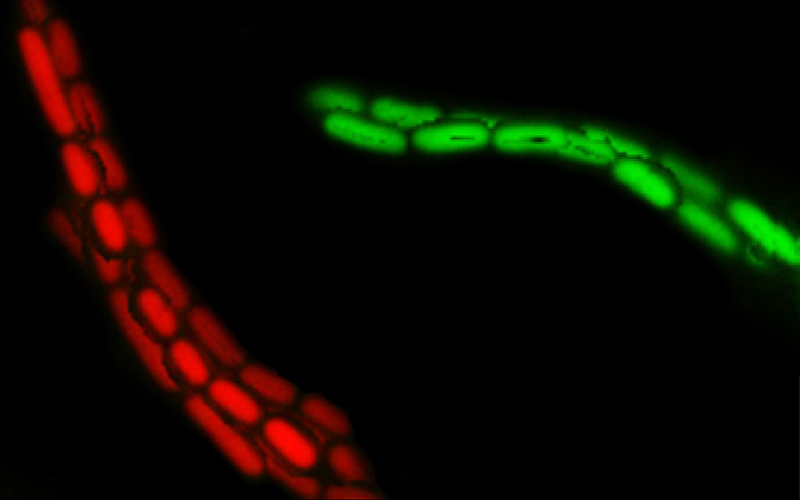

IgA ‘enchains’ dividing bacteria to form clumps, making them unable to invade the wall of the intestine and infect the body.

Because each enchained clump is made up of progeny of a single bacterium, the enchainment also prevents genetic exchange or ‘bacterial sex’ between bacteria in different clumps. Researchers say these vaccinations could be harnessed to decelerate the spread of antibiotic resistance genes.

The work was conducted by an international team of researchers, jointly led by Dr Emma Slack and Professor Wolf-Dietrich Hardt from ETH Zurich, Switzerland and Gates Cambrige Alumnus Dr Douglas Brumley [2009] from the University of Melbourne. It is published in print today in the journal Nature*.

The team studied Salmonella – a bacterium causing food poisoning – and used in vivo experiments and mathematical modeling to show that secretory IgA works very differently than scientists previously believed.

“By using an interdisciplinary approach involving lab-based science and mathematical modeling, we discovered the mechanism behind the clumping,” said Dr Brumley, who did his PhD in Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics at the University of Cambridge where he also combined biophysics, fluid dynamics and microbial ecology.

Other researchers have shown that antibodies and bacteria can clump, a process known as classical agglutination. However, this only occurs when they are present in high numbers and often come into contact with each other (like in the test tube).

“During typical infections, pathogenic bacteria are in such low concentrations that they rarely encounter one another. It would be like accidentally bumping into people you know at a music festival,” said Dr Brumley who is currently a Lecturer in Applied Mathematics at the University of Melbourne.

“It turned out that the driving force behind the formation of the clumps was the Salmonella pathogens’ own growth.

“When the bacteria reproduce to form daughter cells, the IgA antibodies attach themselves so strongly to bacteria that the cells cannot separate. Although the enchained bacteria can continue to multiply, all their offspring remain trapped in these clumps, rendering them largely harmless to the host.”

Dr Slack from ETH said that fighting intestinal infections using vaccination has several advantages. The antibody-bacteria clumps cannot approach the intestinal wall, therefore preventing the intestinal mucosa from becoming inflamed.

“The intestine also gets rid of the clumps quickly, and after a few days they are cleared in the faeces,” Dr Slack said.

“The clever thing about clump formation is that the antibodies don’t kill the bacteria, which in the worst case could lead to a violent immune response. They simply prevent the microbes from interacting with the host, among themselves or with close relatives,” added Professor Wolf-Dietrich Hardt from ETH Zurich, a co-author on the study.

By preventing interaction of the bacteria, intestinal vaccination could also help to overcome the antibiotic resistance crisis.

Bacteria often exchange genes in the form of plasmids (ring-shaped DNA molecules), which frequently carry the feared antibiotic resistance genes. To exchange plasmids, however, the bacterial cells have to touch, which they can’t do if they are stuck in separate clumps.

“Vaccination also decreases the incidence of diseases potentially requiring antibiotic usage, which would automatically reduce the development and spread of resistance to antibiotics”, added Dr Slack.

The team suggest that this strategy could also be used against the pathogens causing other intestinal diseases such as Shigella that causes dysentery or Enterotoxigenic E. coli.

*Moor K et al. High-avidity IgA protects the intestine by enchaining growing bacteria, published in Nature. Picture credit: Two clumped clones (red and green) of salmonella are held together by IgA antibodies. (Image: Emma Slack / ScopeM, ETH Zurich)

Douglas Brumley

- Alumni

- Australia

- 2009 PhD Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics

- Trinity College