New study on ancient DNA reveals genetic ‘continuity’ between Stone Age and modern populations in East Asia.

Our work suggests that ethnic groups with traditional societies and deep roots across eastern Russia and China form a strong genetic lineage descending directly from the early Neolithic hunter-gatherers who inhabited the same region thousands of years previously

Veronika Siska

Researchers working on ancient DNA extracted from human remains interred almost 8,000 years ago in a cave in the Russian Far East have found that the genetic make-up of certain modern East Asian populations closely resemble that of their hunter-gatherer ancestors.

The study, whose lead author is Gates Cambridge Scholar Veronika Siska, is published in the journal Science Advances and is the first to obtain nuclear genome data from ancient East Asia and compare the results to modern populations.

The findings indicate that there was no major migratory interruption, or "population turnover", for well over seven millennia. Consequently, some contemporary ethnic groups share a remarkable genetic similarity to Stone Age hunters that once roamed the same region.

The high “genetic continuity” in East Asia is in stark contrast to most of Western Europe, where sustained migrations of early farmers from the Levant overwhelmed hunter-gatherer populations. This was followed by a wave of horse riders from Central Asia during the Bronze Age. Both events were likely driven by the success of emerging technologies such as agriculture and metallurgy.

The new research shows that, at least for part of East Asia, the story differs with little genetic disruption in populations since the early Neolithic period.

Despite being separated by a vast expanse of history, this has allowed an exceptional genetic proximity between the Ulchi people of the Amur Basin, near where Russia borders China and North Korea, and the ancient hunter-gatherers laid to rest in a cave close to the Ulchi’s native land.

The researchers suggest that the sheer scale of East Asia and dramatic variations in its climate may have prevented the sweeping influence of Neolithic agriculture and the accompanying migrations that replaced hunter-gatherers across much of Europe. They note that the Ulchi retained their hunter-fisher-gatherer lifestyle until recent times.

"Genetically speaking, the populations across northern East Asia have changed very little for around eight thousand years,” said senior author Andrea Manica from the University of Cambridge, who conducted the work with an international team, including colleagues from Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology in Korea, and Trinity College Dublin and University College Dublin in Ireland.

"Once we accounted for some local intermingling, the Ulchi and the ancient hunter-gatherers appear to be almost the same population from a genetic point of view, even though there are thousands of years between them."

The new study also provides further support for the dual origin theory of modern Japanese populations: that they descend from a combination of hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists that eventually brought wet rice farming from southern China. A similar pattern is also found in neighbouring Koreans, who are genetically very similar to Japanese.

However, Manica says that much more DNA data from Neolithic China is required to pinpoint the origin of the agriculturalists involved in this mixture.

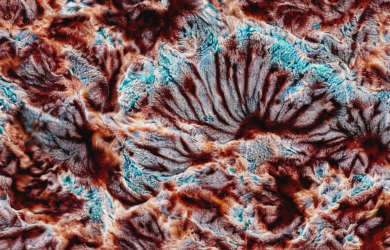

The team from Trinity College Dublin were responsible for extracting DNA from the remains, which were found in a cave known as Devil’s Gate [pictured]. Situated in a mountainous area close to the far eastern coast of Russia that faces northern Japan, the cave was first excavated by a Soviet team in 1973.

Along with hundreds of stone and bone tools, the carbonised wood of a former dwelling, and woven wild grass that is one of the earliest examples of a textile, were the incomplete bodies of five humans.

If ancient DNA can be found on sufficiently preserved remains, sequencing it involves sifting through the contamination of millennia. The best samples for analysis from Devil’s Gate were obtained from the skulls of two females: one in her early 20s, the other close to 50. The site itself dates back over 9,000 years, but the two women are estimated to have died around 7,700 years ago.

Researchers were able to glean the most from the middle-aged woman. Her DNA revealed she likely had brown eyes and thick, straight hair. She almost certainly lacked the ability to tolerate lactose, but was unlikely to have suffered from alcohol flush: the skin reaction to alcohol now common across East Asia.

While the Devil’s Gate samples show high genetic affinity to the Ulchi, fishermen from the same area who speak the Tungusic language, they are also close to other Tungusic-speaking populations in present-day China, such as the Oroqen and Hezhen.

"These are ethnic groups with traditional societies and deep roots across eastern Russia and China, whose culture, language and populations are rapidly dwindling,” said Siska [2014], who is doing a PhD in Zoology.

“Our work suggests that these groups form a strong genetic lineage descending directly from the early Neolithic hunter-gatherers who inhabited the same region thousands of years previously.”

Veronika Siska

- Alumni

- Hungary

- 2014 PhD Zoology

- Trinity College

After graduating from the Budapest University of Technology and Economics in 2012 with a Bsc degree in Physics, I decided to switch to mathematical biology on the international Erasmus Mundus Masters in Complex Systems Science programme. My research here focused on epidemiological modelling, with applications on Tasmanian Devil Facial Tumour Disease and human influenza, both fundamentally influenced by the dynamics of genetically different strains. During my PhD, I aim to create a spatially explicit population genetics framework to explore how different selection across the species range can affect the spread of beneficial traits, using recent genetic data. Aside from applications, such as shaping efforts in conservation ecology or searching for genes of medical importance by distinguishing between effects of demographic events and selection, it will also help us reconstruct human demographic history and understand how species can rapidly adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Previous Education

University of Warwick 2013

University of Gothenburg 2012

Budapest University of Technology and Economics 2009