Christopher Kirchhoff talks about his new book on defence innovation and about his time as a Gates Cambridge Scholar.

The result of my meeting scholars from a profoundly international class is that I myself became more internationalist in orientation and came to understand my own country, the United States, in new ways.

Christopher Kirchhoff

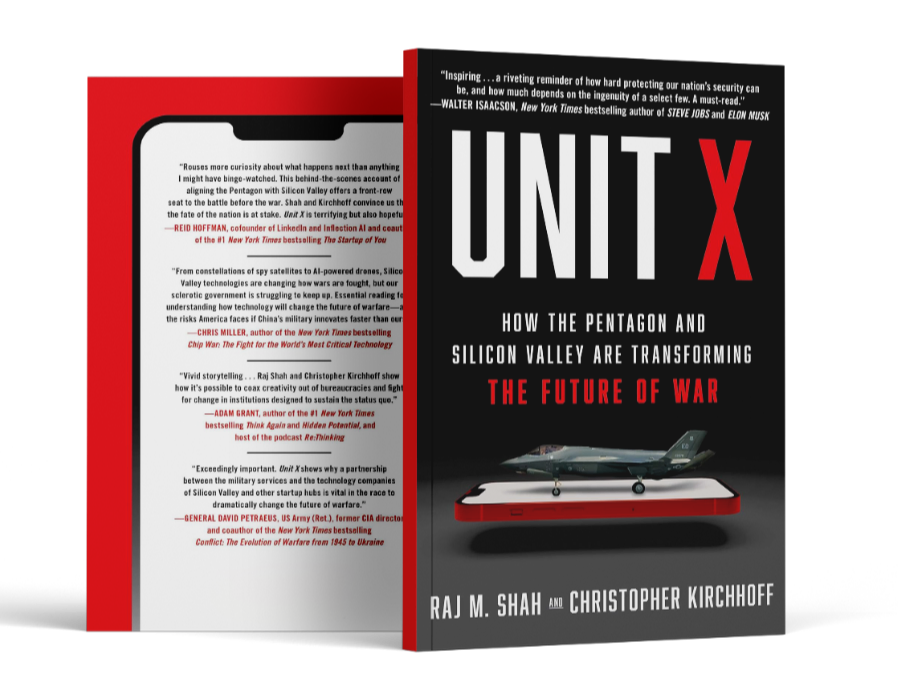

Christopher Kirchhoff [2001] has just co-authored a book which gives an inside look at Unit X, the elite unit within the Pentagon that he and co-author Raj M Shah founded. It brings Silicon Valley’s cutting-edge technology to America’s military. The book Unit X: How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley Are Transforming the Future of War, was published in the US in July and is out in the UK in August. The two men know more about Unit X than most as they co-founded it in 2016.

Kirchhoff had already served as a strategist in President Obama‘s National Security Council and as the civilian assistant to General Martin Dempsey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, when he was appointed by the Secretary of Defense to create and launch the Pentagon’s Silicon Valley Office. He speaks to Gates Cambridge about how the book came about and much more.

Gates Cambridge: What motivated you to write this book at this particular time?

Christopher Kirchhoff: We stand at the precipice of a revolution in military affairs today. The Ukrainian military recently evacuated all 31 of the US provided M1AI Abrams tanks after a quarter of them were destroyed by Russian kamikaze drones. The withdrawal of the world’s most advanced battle tank in an AI-powered drone war foretells the end of a century of manned mechanised warfare. If the US and its allies can’t figure out ways to defend against new AI-powered weapons, the military advantage we have enjoyed will rapidly erode.

GC: What can AI bring to the defence world and can you give examples of some recent innovations?

CK: Autonomous weapons systems are going global. Hezbollah’s use of loitering munitions has displaced 85,000 Israelis after the Israeli military proved unable to defend the first 10 miles of its territory south of the Lebanese border. Houthi rebels are deploying autonomous sea drones to hold hostage 12 percent of global shipping that passes through the Red Sea. Most strikingly, Hamas used quadcopters to disable generators powering the Israeli border towers, enabling 1,500 fighters to pour over a modern-day Maginot line and kill over 1,000 Israelis, precipitating the worst eruption of violence in the Middle East since the 1973 Arab-Israeli war.

The best way to fight AI-powered weapons is with better AI-powered weapons. The US military is starting down the path with its “Replicator Initiative” – but really that is only at the beginning of experimenting with how AI can bring military advantage.

GC: Do you think there is not sufficient awareness of the urgency of the issues when it comes to the role of technology innovation in defence?

CK: Most people don’t realise there are entirely separate systems of technological production, one for the military and one for everything else. Take, for example, the F-35, the Apex predator of the sky. The 5th generation stealth fighter is known as a “flying computer” for its ability to fuse sensor data with advanced weapons. Yet the F-35 has a slower processor than the iPhone.

How could a $2 trillion dollar programme field fighter airplanes with less clock speed than what we carry around in our pocket? The F-35 design was frozen in 2001, the year the Pentagon awarded its contract to Lockheed Martin, and its combat requirements were finalised even earlier, in the 1990s. Yet the F-35 only became fully operational in 2016. By the time the first F-35 was rolling down the runway, technology’s state of the art had already flown by it. The iPhone was in its fifth iteration. This year the iPhone 16 arrives. Today, the F-35 is haltingly progressing through its third technology upgrade, with quad core processors in testing that were already in smartphones a decade ago.

Remaking the military’s bespoke system of production to mirror the system that produces commercial products is the mission of Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), the Pentagon’s Silicon Valley office.

GC: Do you think there is any chance of de-escalating the AI weapons arms race at a time of so little trust and open conflict, given big concerns about autonomous weapons [LAWs]?

CK: The best way to prevent war is to deter one from ever breaking out. AI weapons are awful things — they can cause such horrific harm to humans. These are weapons we never hope to have to use. Yet if we don’t have them, and we end up in a conflict where they are used against us, we will lose.

GC: How difficult was it to bridge the divide between tech and defence? Are there any stand-out moments where things changed?

CK: Ten years ago venture capitalists discouraged entrepreneurs they backed from working with the government. Pentagon contracts often took 18 to 24 months to award. Even if a start-up’s technology worked, another firm with better lobbyists could easily win subsequent production contracts.

Today a new generation of defence unicorns minted by DIU are creating AI-powered autonomous systems more advanced than anything the military-industrial complex has produced, including drone manufacturer Skydio (valuation $2.2B), autonomy company Sheild.ai ($2.7B), Joby Aviation ($5B), and Anduril ($12.5B).

None of the new defence unicorns would exist had a brilliant 29-year-old acquisition specialist named Lauren Dailey not exploited a loophole in the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act to invent a whole new way for DIU to contract in as little as two weeks. With the Secretary of Defense’s support, we codified this new method in three weeks, opening the floodgate to start-ups and tech firms that today have used it to provide the Pentagon with $70 billion of technology.

This is the achievement of which I am most proud of, and which has done the most to change the culture of the US military.

GC: What do tech start-ups bring that larger defence corporates can’t?

CK: Agility, speed and efficiency.

GC: What does it take to stay dominant in a fast-changing geopolitical landscape?

CK: A willingness to move beyond paradigms of war-fighting that technology has suddenly overtaken. The Pentagon overwhelmingly spends its dollars on legacy weapons systems. It continues to buy tanks, ships and aircraft carriers that new generations of weapons – autonomous and hypersonic – can demonstrably kill. It’s time that America and its allies commit to a new approach.

GC: How did you come to be part of the first Gates Cambridge class?

CK: The instant I knew everything changed was when I picked up a DHL package sent by the Trust. It was fat enough that I knew it wouldn’t be a rejection letter. I almost melted with glee.

GC: What was it like to be in the inaugural class?

CK: The Trust’s first Provost, Gordon Johnson, described Cambridge as a safe place for Americans to meet Europeans. He was right. I made so many close friends with scholars from Europe and around the world, and went home with many of them, to France, South Africa, Switzerland and beyond. The result of my meeting scholars from a profoundly international class is that I myself became more internationalist in orientation and came to understand my own country, the United States, in new ways. I am so profoundly grateful for that – it is something I carried with me on my work on geopolitics and national security.

GC: What was your PhD about?

CK: I wrote about breakdowns in the national security state, like 9/11, and commissions that play an important role in fixing them.

GC: How did you get involved in disaster management?

CK: My first job out of college – which I took a leave from my Gates scholarship to pursue – was on the Space Shuttle Columbia Accident Investigation in 2003. I had studied technological breakdowns and got hired as the investigation’s report writer. It was an incredible experience for a kid whose first dream was to become an astronaut. In part because of that experience I later worked on major US government reports on other breakdowns and surprises, including the US official history of Iraq Reconstruction, Hard Lessons, and the Obama Administration’s Big Data Report and after action report on Ebola, which foretold many of the difficulties we encountered during Covid.

GC: Are there any common threads in the different disasters you have worked on?

CK: Complex systems break down in complex ways — with both technical, human and organisational factors at play.

GC: What was it like to work in the Obama government and to be the highest ranking openly gay adviser in the US military?

CK: Politics is personal. So it was quite something to be in the Pentagon during the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” [the set of policies, laws, and regulations governing how the US military dealt with gay, lesbian, and bisexual service members]. I’ll never forget wearing a gay pride lapel pin for the Pentagon’s first pride celebration. There were other incredible moments of leadership. Shortly after the repeal, I was at the holiday party of my new boss, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. There was still grumbling at the time among senior officers about the repeal. The Chairman was having none of it. To signal where he stood, he grabbed me and my husband and made a point of talking to us first in front of everyone else at his party – with half the US cabinet, the White House Chief of Staff and the Joint Chiefs all looking on. It was so meaningful to be able to be part of historic change just by showing up and being who I was.

GC: How did that lead to your work in Defense Innovation Unit X?

CK: I had focused on technology issues for a long time, so when it came time to launch the Pentagon’s Silicon Valley office, Secretary of Defense Ash Carter asked me to lead the working group that developed the concept. Not long after that, Ash Carter informed me that I would soon be moving to California at his request, to lead Defense Innovation Unit X. It caused something of a wardrobe crisis. At the time I had five suits and only one pair of jeans. By the time I arrived in San Francisco I had five pairs of jeans and one suit, which, of course, I never wore.

*Find out more information about the book here and about Christopher here. Read an excerpt from the book in the Atlantic here.