New sustainable solutions are needed to address a problem that affects two thirds of urban residents in India.

The magnitude of India’s sanitation crisis may be summed in one sentence: two-thirds of urban residents do not have a toilet or access to the sewer grid, and over 600 million people in rural and urban areas defecate in the open. Where the grid does not serve toilets, faeces is periodically collected from unsustainable septic tanks and pit latrines to be deposited in open areas, landfill sites, lakes and freshwater sources. The health consequences are immense. Health costs associated with poor or unavailable sanitation cost India six per cent of her GDP.

Unplanned urbanisation

India proposes to address the sanitation crisis head on. Through the Clean India Initiative launched last year, more than ten million toilets are proposed. The initiative also aims to eliminate open defecation in another four years. The question here is not ‘why’, but ‘how’?

In following the beaten path of the sewer grid, developing nations confront three southern limitations. Firstly, urbanisation beats network growth big time. No city in India offers a ubiquitous grid; less than half of Delhi, Bengaluru, and Hyderabad have plug-and-play toilets. The wait for the grid is at least two generations long. This is akin to a doctor informing a patient with palpitations that he or she will have to wait for 30 years for an appointment! Do this to 600 million people and we can only imagine the magnitude of the sanitation crisis.

This brings us to the second limitation. Tax redistribution at the going rate is grossly inadequate. While urban India needs to invest USD 40 billion over 20 years in the grid, USD 825 million per annum was budgeted by all levels of government for the past five years for sewer connectivity. To bolster investment on sanitation, the Government of India has from the 15th of November this year introduced a Clean India levy of 0.5% on top of their existing service tax of 14%. It is estimated that the increase in service tax rate will bring in USD 75 million annually to build toilets across the country. Nonetheless, there will be a long wait. And what about the fact that urbanisation will add 300 million more residents over the next 20 years? This means the network will always be playing catch-up.

Thirdly, India's urban public finance strategy means that property tax, the local revenue mainstay, accounts for just half a per cent of national GDP and cannot finance the sanitation needs of the nation.

Two Sustainable South solutions

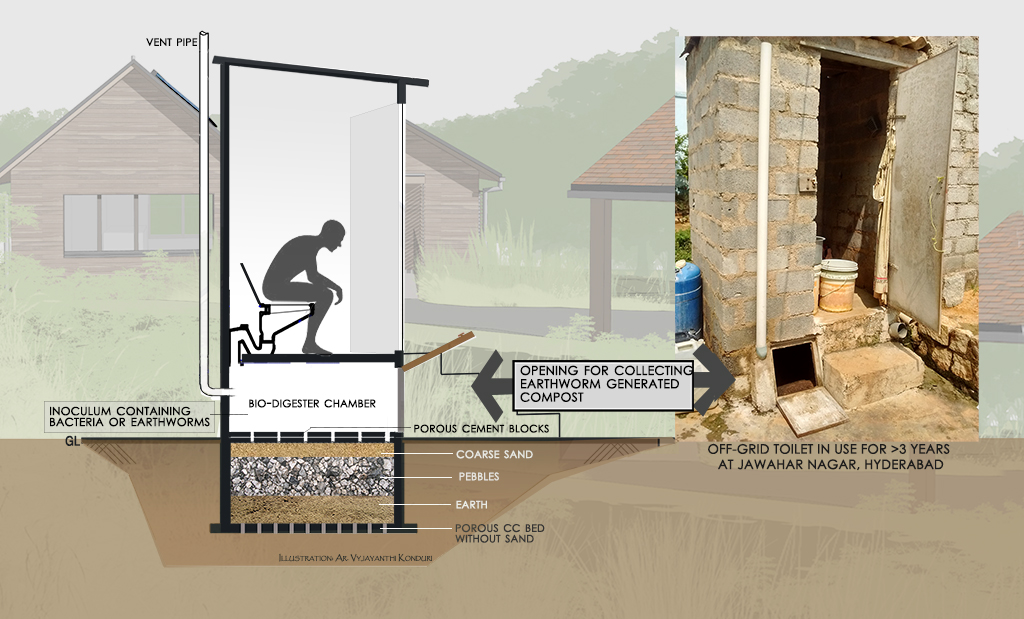

India cannot incessantly wait for something to be done. Two recently developed solutions should be mentioned. The first, the DRDO Bio-Digestion Toilet, a serendipitous innovation born from the need for sanitation for army personnel in the Himalayas, was not invented to address the civilian sanitation crisis. Soldiers stationed in the high altitude regions of Siachen and Ladakh needed toilets and sustainable disposal of human waste. Scientists at DRDO (Defence Research Development Organisation) chanced upon a strain of bacteria, Psychrophile, on a scientific expedition in Antarctica in the 1990s. They brought home a strain of the bacteria and subsequently developed an inoculum – a microbial consortium comprising of four clusters of bacteria from Antarctica and other low temperature areas.

Following research, the consortium was introduced to makeshift toilets in Siachen and Ladakh. As these bacteria thrive in extreme temperatures, the experiment succeeded and was emulated but largely within the confines of the army establishment. It was not until 2012 that the technology gained ground elsewhere, including on the Indian Railways.

Introduced into a chamber constructed below the toilet, the self-sustaining bacteria feed upon the faeces; the anaerobic process degrades the matter within 48 hours. These odour-free, water-sealed, off-grid toilets are a sustainable alternative to septic tanks and pit latrines, the mainstay of sanitation in the south. The small one-time price to procure the inoculum (USD 120) has the potential to transform Indian urban spaces. More than 50 developers have signed up to build these toilets in various parts of the country and retrofit septic tanks and pit latrines sustainably.

At about the same time the DRDO toilet was available for civilian use in 2012, a retired Chief Engineer from Andhra Pradesh, M Dharma Rao, developed an affordable alternative. The inoculum is replaced by a handful of earthworms that generate compost from faeces. Dharma Rao has constructed a few hundred of these toilets in Hyderabad. Six months of toilet use produces a bucket (10 litre capacity) of compost, thus rendering the toilet maintenance free. Dharma Rao’s innovation scores high on the sustainability index; importantly, the toilet is affordable and costs less than USD 180 to build.

There are probably more undocumented solutions. Exasperatingly, the sanitation crisis may not have attracted the imagination of the global talent pool to develop lasting, affordable solutions. India may want to utilise the remainder of 2015 to scale up manifold innovations such as those discussed. If the years 1974 and 1989 marked important contributions from the south for mobility (Mayor Jamie Lerner’s design of the Bus Rapid Transit System for Curitiba) and municipal budgeting (participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre), the year 2016 should be earmarked for the development of affordable, sustainable and scalable solutions. We cannot afford not to rid settlements of unsustainable pit latrines, septic tanks and open defecation.

*An urban planner by learning and alumnus of Cambridge University, MS Raghavendra [2002 – PhD in Architecture] teaches at Administrative Staff College of India and may be reached at m.raghavendra@gatesscholar.org for a longer version of this piece. He did his PhD on water supply for poor settlements in India and Peru.