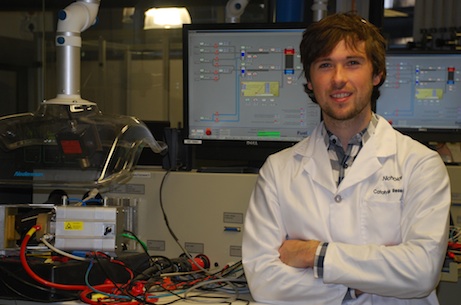

Scholar Elect Nicholas Rice's research will focus on finding working renewable energy solutions for developing countries like his home country, South Africa.

Finding a workable renewable energy solution is a pressing issue for countries like South Africa which are facing urgent development challenges.

Although Nicholas Rice is currently working on the fundamental science needed to address the issue, he hopes that his MPhil at Cambridge, which he begins in the autumn, will allow him to look at the associated social, cultural, political and economic aspects of the problem.

He says: “The traditional way to boost development is to push for nationwide electrification through carbon-based energy, but the problem is that this model is unsustainable and will drive climate change.”

Nicholas is currently working for HySA [Hydrogen South Africa]/Catalysis, a South African government-funded initiative which focuses on hydrogen and fuel cell technology.

He believes hydrogen-powered vehicles have an important role to play in future diversification and the move towards clean energy, and that they have great potential in stationary power applications too.”

His work is focused on the fundamental science of clean energy, but other branches of HySA/Systems are involved in the practical implementation of research, such as building hydrogen-powered forklift trucks.

“Whilst it is very important to focus on long-term technology development, such as fuel cells, I would like to be involved in the development of African-applicable technology which will address short-term development needs sustainably,” he says.

Childhood

Nicholas, who is also currently working as a teaching assistant at the University of Cape Town, has been interested in engineering since early childhood. At the age of eight, he knew he wanted to do chemical engineering.

Born in Johannesburg, he grew up in Cape Town in an artistic family. Apart from his brother, who is also studying engineering, both his parents tend more to the arts than science. Nicholas’ mother studied drama and English and is a classically trained pianist and his English-born father is a film and tv sound technician who played bass guitar in a couple of bands and worked for the BBC, filming events such as Nelson Mandela’s release from prison. When Nicholas was young his father was away a lot, travelling around Africa, Europe and Asia.

Most of his other relatives were in the arts too. Nevertheless, from an early age Nicholas was interested in science and engineering. His parents encouraged a thirst for knowledge and he naturally found himself gravitating towards science, although he played a lot of music and did photography. He adds that he has always been fascinated by the links between science and the arts, especially between music and physics.

At high school Nicholas was part of the audio visual team, sang in the choir, played trombone in a brass band and guitar in a rock band. He also joined the Edmund Rice Society which organised debates in underpriveleged areas and was involved in Interact Club, a Rotary-guided organisation which is based at high school level for outreach.

His school encouraged a broad outlook on the world. This included sports sessions with students from township schools.

Nicholas chose to do chemical engineering at the University of Cape Town because it brought together maths, physics and chemistry and because he wanted to do something which had a practical application.

Diffusion

The course was four years and in his fourth year he did a three-month research project which involved developing a technique for teaching diffusion by measuring diffusivities using just mobile phone cameras and a laptop.

It’s a topic which is covered in the engineering syllabus, but Nicholas says studying diffusion in a lab course requires sophisticated and expensive equipment which is often unavailable due to cost and the size of classes.

“The principle of diffusion affects a lot of things in chemical engineering design. It’s vital to get a good understanding of it, but it’s a very difficult subject to demonstrate practically,” he says.

He and his research partner are writing up a paper on their work which they hope to submit to a peer-reviewed journal. They also hope that their method will be used in undergraduate curricula to help students grapple with diffusion.

The method was developed during consultations with their supervisor who had the idea to visualise diffusion through the use of coloured substances and suggested mobile phone cameras. Nicholas and his partner came up with a simple and inexpensive way to construct the apparatus and conduct the experiments in a home setting.

“A spectrophotometer can cost thousands of pounds, but we did a survey and found that most students have access to a mobile phone camera,” he says.

His lecturer will be the first to trial the method on his mass transfer course.

Cambridge

Nicholas chose to apply to the University of Cambridge because of its reputation at the forefront of energy research. Although the Skype connection broke down during his interview for the Gates Cambridge Scholarship, he was accepted and will become the first chemical engineering graduate from the University of Cape Town to win the Scholarship.

In addition to his academic work at the University, he has been involved in a broad range of other activities, including photography and working for Engineers Without Borders on the African Community Projects in Belhar, a poor suburb of Cape Town. This involved working with a local community centre which wanted to improve its agricultural activities. He helped design an egg incubator and a renewable water heater for an aquaculture project to sell tilapia fish.

“It was a reality check,” he says. “It showed me the hard reality of the lives of so many people in my country and gave me the opportunity to help and that is something I want to continue with my research.”