A new study led by Andres Alfonso Rojas marks the first in-depth examination of fossil snakes in Colombia in the last 25 years

Paleontologists have moved a step closer to understanding the life of an enigmatic ancient snake that roamed South America between 16 to 5 million years ago, a geologic epoch known as Middle to Late Miocene.

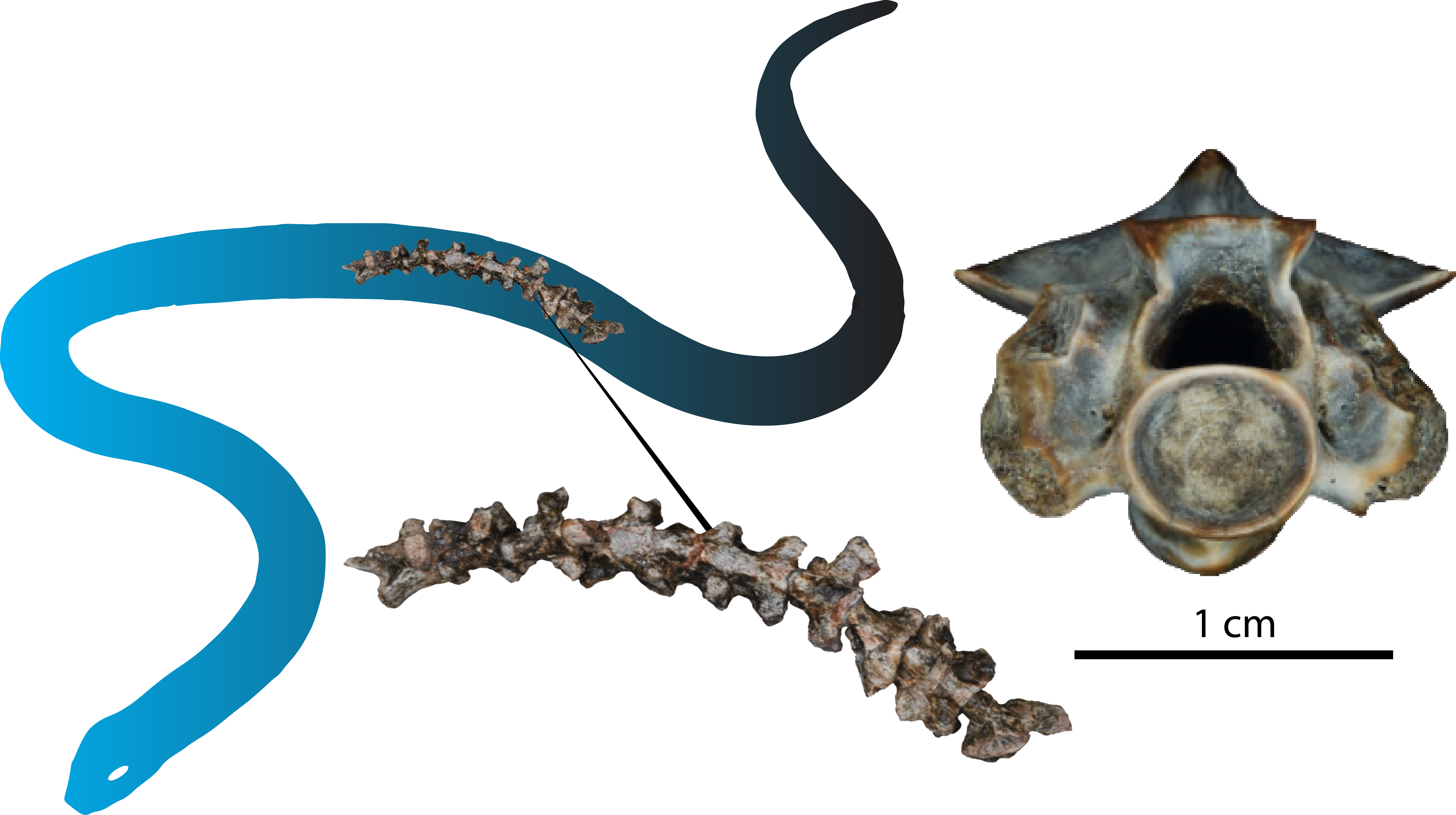

Colombophis, which means “snake of Colombia” in Greek, is an extinct genus of snakes closely related to extant American pipe snakes from the Amazon rainforest. The first fossils of this genus were discovered in 1977 in Villavieja, located in the La Tatacoa desert region of south-central Colombia. These fossils, consisting of 40 fragmentary vertebrae, led to the identification of the first species called Colombophis portai. Subsequently, another species, Colombophis spinosus, was described based on fossils found in Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela.

A new study, led by Gates Cambridge Scholar Andrés Alfonso-Rojas [2022] and published in the journal Geodiversitas, marks the first in-depth examination of fossil snakes conducted in the last 25 years of paleontological research in the La Tatacoa desert in Colombia.

The classification of Colomophis among other snake groups has been a subject of debate since its discovery. Its backbones exhibit morphological features similar to those of today’s American and Asian pipe snakes (Aniilidae and Uropeltoidea). Recently, the discovery of several new fossils in the La Tatacoa desert, belonging to at least 50 different individuals of this genus, provided an opportunity for paleontologists to re-evaluate its affinities. On analysing these fossils, the research team found that the two known species of Colombophis, Colombophis portai and Colombophis spinosus, share more similarities than previously thought. For instance, they exhibit similarities in the degree of depression of the neural arch and the length-width proportion of the vertebral centrum. However, significant differences still exist between the two species, such as the more elongated vertebrae in C. portai compared to C. spinosus.

Although most of the new fossils described are fragmentary, the researchers argue that they support the classification of Colombophis within the alethinophidian snakes, a group that encompasses all snakes except blind snakes and thread snakes. Additionally, the researchers suggest that, despite sharing a vertebral morphology with fossorial snakes (those with an underground lifestyle), considering the vertebrae size, the snakes are likely to have lived on the surface of the earth.

Although most of the new fossils described are fragmentary, the researchers argue that they support the classification of Colombophis within the alethinophidian snakes, a group that encompasses all snakes except blind snakes and thread snakes. Additionally, the researchers suggest that, despite sharing a vertebral morphology with fossorial snakes (those with an underground lifestyle), considering the vertebrae size, the snakes are likely to have lived on the surface of the earth.

Lead researcher PhD student Andrés Rojas, stated: “The fossils of Colombophis are relatively large compared to those of snakes that typically live underground. We estimate a body size of around 1.5 to 2 metres (five to six feet), which is similar to the size of ground-dwelling snakes like boas or some colubroids.”

In addition to expanding our understanding of this fossil snake, the study also sheds light on the vertebral anatomy and intracolumnar variation in Colombophis. Notably, the presence of parazygantral foramina (fissures) in the vertebrae of Colombophis, similar to those observed in another ancient snake family called Madtsoidae, was discovered for the first time.

Andrés commented: “Although these new fossils have provided us with valuable insights, it is evident that the information we can glean from isolated vertebrae is limited. Further fieldwork leading to the discovery of more complete specimens will be necessary to gain a better understanding of the ecological and phylogenetic connections of this enigmatic fossil snake.”

*Picture credit: Dr Edwin Cadena. The top picture pictures shows show Dra. Catalina Suarez, Diego Urueña and Andrés (from right to left), collecting fossils at La Tatacoa Desert. The embedded photo depicts a sketch of a snake and the fossils of Colombophis.