Study led by Kevin Nead shows men given ADT were nearly twice as likely to get Alzheimer's.

It’s hard to determine the precise amount of increased risk in just one study and important to note that this study does not prove causation. But considering the already-high prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in older men, any increased risk would have significant public health implications.

Kevin Nead

Men taking androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for prostate cancer were almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in the years that followed than those who didn’t undergo the therapy, an analysis of medical records from two large hospital systems by Penn Medicine and Stanford University researchers, led by a Gates Cambridge Alumnus, has shown. Men with the longest durations of ADT were even more likely to get an Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

The findings, published in the December 7 issue of The Journal of Clinical Oncology, do not prove that ADT increases Alzheimer’s risk. But the authors say they clearly point to that possibility, and are consistent with other evidence that low levels of testosterone may weaken the aging brain’s resistance to Alzheimer’s.

“We wanted to contribute to the discussion regarding the relative risks and benefits of ADT, and no one had yet looked at the association between ADT and Alzheimer’s disease,” said lead author Kevin T. Nead [2011], MD, MPhil, a Gates Cambridge Alumnus and now resident in the department of Radiation Oncology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. “Based on the results of our study, an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease is a potential adverse effect of ADT, but further research is needed before considering changes to clinical practice.”

Androgens (male hormones) normally play a key role in stimulating prostate cell growth. Thus, therapies that shut down androgen production or activity are often used in treating prostate tumours.

Drastically reducing androgen activity can have adverse side-effects, however. Studies have found associations between low androgen levels (chiefly low testosterone levels) and impotence, obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease and depression. Research in recent years also has linked low testosterone to cognitive deficits, and has shown that men with Alzheimer’s tend to have lower testosterone levels, compared to men of the same age who don’t have the disease.

For the study, Nead, who is also a fellow at Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, co-author Samuel Swisher-McClure, senior author Nigam Shah and their colleagues at Stanford’s School of Medicine evaluated two large sets of medical records, one from the Stanford health system and the other from Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City. Together the records covered about five million patients, of whom 16,888 received a diagnosis of prostate cancer and met all the other criteria for the study.

Of the 16,888 prostate cancer patients, about 2,400 had received ADT and had the necessary follow-up records. Nead and his colleagues compared these ADT patients with a control group of non-ADT prostate cancer patients, matched according to age and other factors.

By two different types of statistical analysis, the team showed that the ADT group, compared to the control group, had significantly more Alzheimer’s diagnoses in the years following the initiation of androgen-lowering therapy. By the most sophisticated measure, members of the ADT group were about 88 percent more likely to get Alzheimer’s during the follow-up period.

The analyses also suggested a “dose-response effect.” The longer individuals underwent ADT the greater their risk of Alzheimer’s disease, they found. The longer-duration ADT patients also had more than double the Alzheimer’s risk of non-ADT controls.

The findings held up when the patient groups from the two hospital systems were considered separately.

“It’s hard to determine the precise amount of increased risk in just one study and important to note that this study does not prove causation,” said Nead, who did his MPhil in Epidemiology at the University of Cambridge. “But considering the already-high prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in older men, any increased risk would have significant public health implications.”

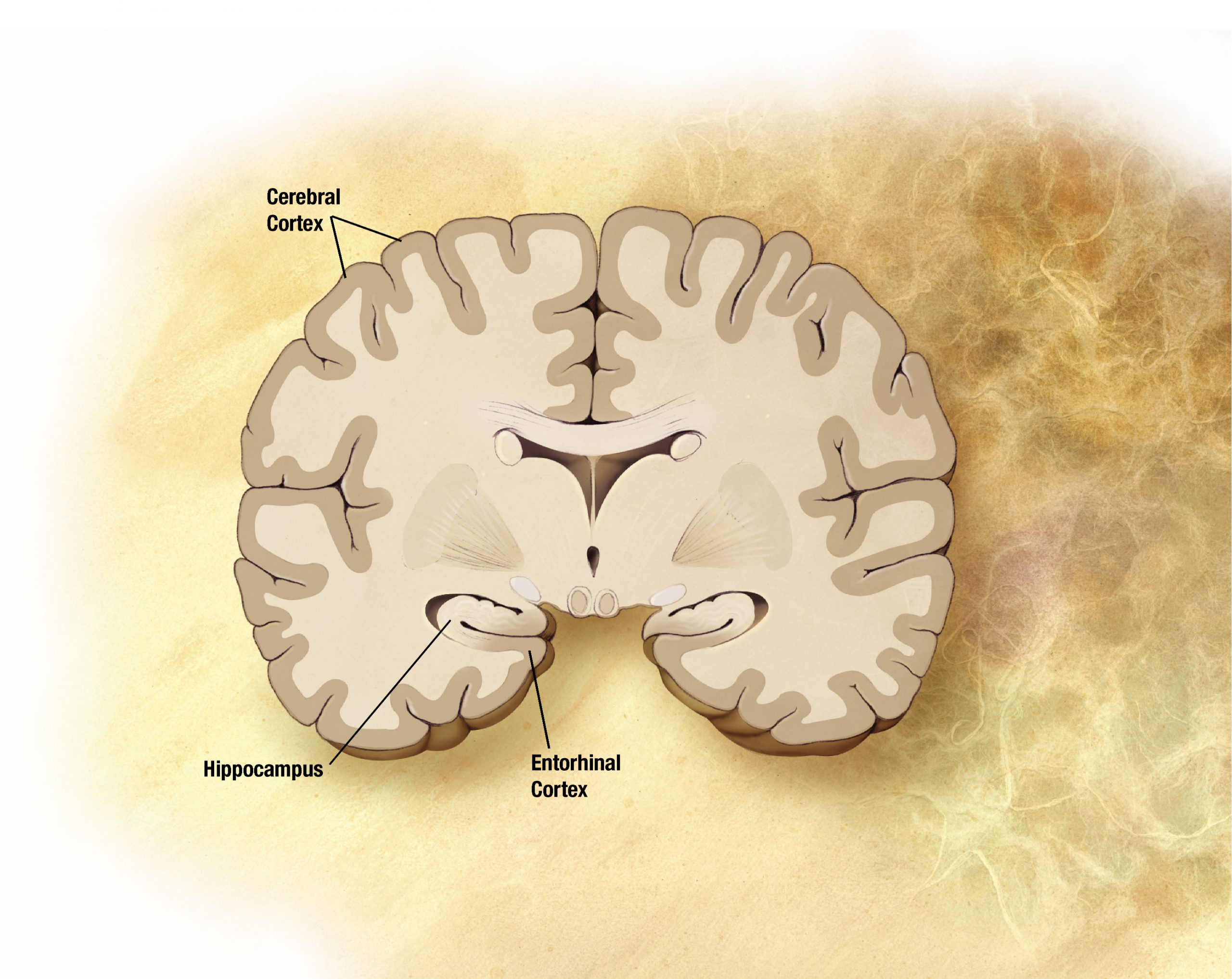

How low testosterone would lead to increased Alzheimer’s risk isn’t precisely known, but there is some evidence that testosterone has a general protective effect on brain cells, so that lowering testosterone would leave the brain less able to resist the processes leading to Alzheimer’s dementia. Studies in mice and in humans also have suggested that lower testosterone levels may allow greater production of the Alzheimer’s protein amyloid beta. Moreover, low testosterone may increase Alzheimer’s risk indirectly, by promoting conditions such as diabetes and atherosclerosis that are known to predispose to Alzheimer’s.

In any case, Nead says a randomised trial is ultimately needed to determine whether ADT does increase Alzheimer’s risk. He and his colleagues are now hoping to examine this association in large cancer registry datasets to see which subgroups of patients might be at greatest risk.

*Picture credit of brain showing effects of Alzheimer's: Wikipedia.