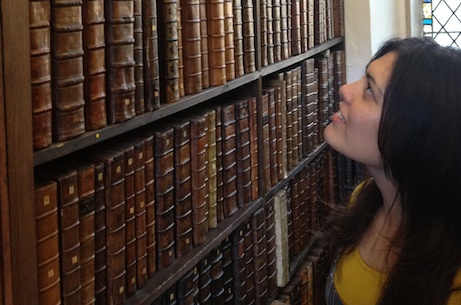

Elsa Treviño's resarch examines the role of the writer in 21st century Latin America, a doubly relevant subject for her since she is also a writer herself.

What is the role of the Latin American writer today? In the 20th century, Mexican literature was heavily concerned with nation building, and narratives about national identity were manipulated by an authoritarian one-party political system.

However, the turn of the century in Mexico brought about major sociopolitical transformations due to the neoliberal turn in Latin America, the country’s bumpy transition to democracy and the Zapatista uprising.

Elsa Treviño Ramírez’s research focuses on how fictional storytelling makes sense of the shifting cultural and political reality of Mexico today. “I study novels published from 1995 onwards,” she explains. “The dawn of the new millennium was a period of rapid cultural change and literature of this time reflects that instability. Writers had to create a new language to talk about the effects that NAFTA, democracy and contemporary globalisation had on reshaping the texture of the nation.”

Her research looks at how 21st century Mexican novels use literary spaces to talk about individual identities beyond the Mexican nation. For her, current literature reflects the changes in our sense of belonging in the midst of a crisis of the traditional nation-state. “There is a lot of questioning about the role intellectuals and artists will have under the new ‘postnational’ set-up,” she comments.

Writing

The issue of what modern literature is for is doubly of interest to Elsa since she is also a writer: she has published several short stories, winning the first prize for micro-fiction in a competition held by the Italian journal Quaderni Ibero Americani; has co-scripted an award-winning screenplay about how new artists are being held back by the cultural market; and written and created a TV series, which will air later this year in Mexico.

Elsa [2009] has long been interested in questioning the world around her through her writing. “When I was seven, I told my Sunday school teachers I would dedicate my books to them,” she says. One of four children born in Celaya in central Mexico, Elsa’s father is CEO of a food company and her mother teaches cooking in schools.

As a child, her father would bring books back to the house and try to introduce his children to a wider world than the one immediately available to them. “He wanted us to have a broader mind-set since we lived in a small city,” says Elsa.

She grew up reading anything she could get her hands on, for instance, books owned by her relatives. At her friends’ houses she would be scanning their books while they played Nintendo. She and her brothers attended an alternative school which taught using plays and music and had its own farm. In high school, Elsa also benefitted from unorthodox approaches to learning. She was in an advanced class for fully bilingual students where her English teacher would have them watch art films, read Nobel Prize winning authors and Australian aboriginal writers and analyse Pink Floyd lyrics in the same way as poems by T.S. Eliot and Walt Whitman, something which was “uncommon” in the context she grew up in.

International relations

Elsa had always wanted to study literature, but everyone told her it was not the way to a successful livelihood so she started her university career studying communications at the Tecnológico de Monterrey. Nevertheless, she didn’t find the course stimulating enough so she switched to a major in international relations in her second year. “I chose that degree because you had to take multiple literature classes as a means to understand the cultural context of different countries,” she says. The degree included history, politics, business and literature. In her third year she did a study trip to Clermont-Ferrand, France, where she studied business and marketing. She also used that time to travel widely around Europe and to qualify for a certificate in bicultural studies and she co-founded a student association which organised a student exchange with the Magellan programme of the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland.

With the highest scores in her class, she was offered a full scholarship to do a masters course in the humanities. “That was when my life changed forever,” she says. The head of the programme told her she needed to build up her knowledge of literary theory quickly, which she did. “It was one of the most challenging things I’ve ever done. I loved literature, but I didn’t know how to formally study it yet,” she says. The terms of her scholarship meant she had to work as a research assistant for a research chair, helping with the administration of research grants, organising literary conferences and working with the humanities journal Revista de Humanidades. She also taught classics and Latin American literature in a high school for a year and a half. She found the process “frustrating” as it highlighted for her the inequality in the education system between rich and poor. “It was a very privileged school and it was hard not to get exasperated by the reality of how unequal Mexico is,” she says.

Fantasy feature film

Additionally, she had done creative writing classes in the last two years of her undergraduate degree, which stimulated her desire to take writing fiction seriously. During her first year of her masters course she co-wrote a fantasy feature film critiquing the world of art with a friend who submitted the screenplay for a competition where it won first prize. Since then both women have written a TV series about people trapped in limbo where they are trying to come to terms with issues they could not resolve during their lifetimes. “We tried to make it mysterious and surreal. People see the death of someone loved as a loss. We wanted to talk about what those who leave this world lose as well. It’s a sort of carpe diem with a dark twist,” says Elsa.

Motivated by her experience in teaching, she decided to stay in academia, but she was keen to gain a wider perspective. “I had already done literature in Mexico, I needed to look at the bigger Latin American picture,” she says. Influenced by her best friend, she considered Oxbridge. “Most people need someone to tell them they can get into the top schools to try. I was fortunate to have someone who believed in me,” she says. Elsa looked at the Cambridge Latin American Studies programme and was struck by its focus on 21st century Latin American literature, something that at the time was still at its early stages in Mexico.

She was accepted to do an MPhil in Latin American Studies in 2009, supported by a Gates Cambridge Scholarship. Her thesis was on the works of Peruvian writer Santiago Roncagliolo. She also worked on a paper on Mexican web comics and their relation to middle-class democracy and she recently presented her research at a cutting-edge conference on Latin American cyberculture at the University of Liverpool.

Elsa also received a Gates Cambridge Scholarship for her PhD, which is similarly concerned with the role of the educated elite in Mexican life and culture. She has presented her PhD research at conferences in Manchester, London, Oxford, Paris and Buenos Aires and has published journal articles, book reviews and a book chapter on the topic. “I’m really interested in the ambivalent, lukewarm political engagement of the upper and middle classes and their role in artistic production in my country,” she says.

In addition to wanting to bring a global perspective to Mexican literature through studying it from abroad, Elsa is also keen to bring the world to Latin American literature. Aside from her PhD work, she participates in a translation project of Latin American writers into English. “I want to help create wider access to Latin American literature,” she says. “Literature and the arts, from all latitudes, are humankind’s inheritance to every new generation. I feel it’s my duty not only to enjoy it, but also to share it as the serious source of knowledge that it is.”