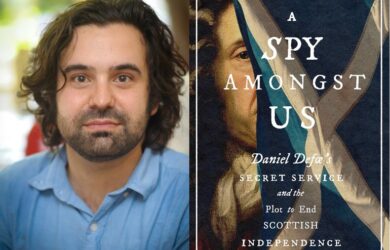

If states can flout international law, does it have any impact, asks Surabhi Ranganathan.

How do states circumvent existing international law to create new norms and does this mean international law has little ability to restrain the most powerful states?

For Gates Cambridge scholar Surabhi Ranganathan, whose PhD focuses on this issue, international law does have a positive impact.

She says: “You can’t conceive of international law in the same way as domestic law. There is no executive or common legislature.” However, she concludes that – as the title of international lawyer Martti Koskenniemi’s famous book goes – international law performs “a gentle civilising effect” on states. She says, for instance, that although the Iraq war broke international rules and was deemed an illegal war by many, the fact that there were international laws to be broken has had consequences in terms of reputation cost and political fall-out for those who were involved.

Her work, which is a commentary on the politics of international legal thought and practice, draws on her previous research and work experience, including an Indian Supreme Court clerkship, internships at UNICEF and UNHCR, the Indian telecom regulator and an environmental action group.

Surabhi has long been interested in international law. She did her law degree at the National Law School of India and at one point she took part in a moot court competition about the splitting up of the former Yugoslavia. “It was fascinating,” she says, “and you needed to understand international politics and economics as well as law. It was multidisciplinary. I found that very creative.”

After graduating, she did a masters in public international law at New York University on an Arthur Vanderbilt Scholarship.

This led to a fellowship at NYU’s Institute for International Law and Justice, where she combined programmatic and research responsibilities for projects on how private military companies operate in the field of conflict and global administrative law.

The Institute brought together people from the US and other governments, people who worked for private military companies, the UN and NGOs.

Surabhi helped to produce a list of principles which should be factored into the regulation of private military companies and which aimed to empower people on the ground more. In Iraq, she says, Iraqi people lack plausible mechanisms for holding private military companies to account. “The legal infrastructure for regulating private military companies is extremely skewed, not helped by the fact that companies are registered in and hired by states other than the one in which they actually operate. We need to focus more on developing local grievance redressal mechanisms, and on scaffolding the industry’s companies own efforts at self-regulation,” she says.

Surabhi [2008], who writes a blog on how international law is portrayed in film, applied to Cambridge in 2007 and was interviewed for a Gates Scholarship by telephone while sitting in her New York office.

She will take up a Junior Research Fellowship at the Lauterpacht Centre for International Law and King’s College, Cambridge, in April. For her post-doctoral project, she is keen to study how international law is used in domestic politics.

Picture credit: creative commons and r-JCO-r.