Devani Singh talks about her new book - the first extended study of the reception of Chaucer’s medieval manuscripts in the early modern period

The new books became a way to extend the life of the old books. They were revitalised by new technology. It is not that the new just replaced the old. Culture works in more complicated ways.

Devani Singh

The first extended study of the reception of Chaucer’s medieval manuscripts in the early modern period offers a fascinating historical precedent for how the move from traditional to digital books can accommodate the new while revitalising the old.

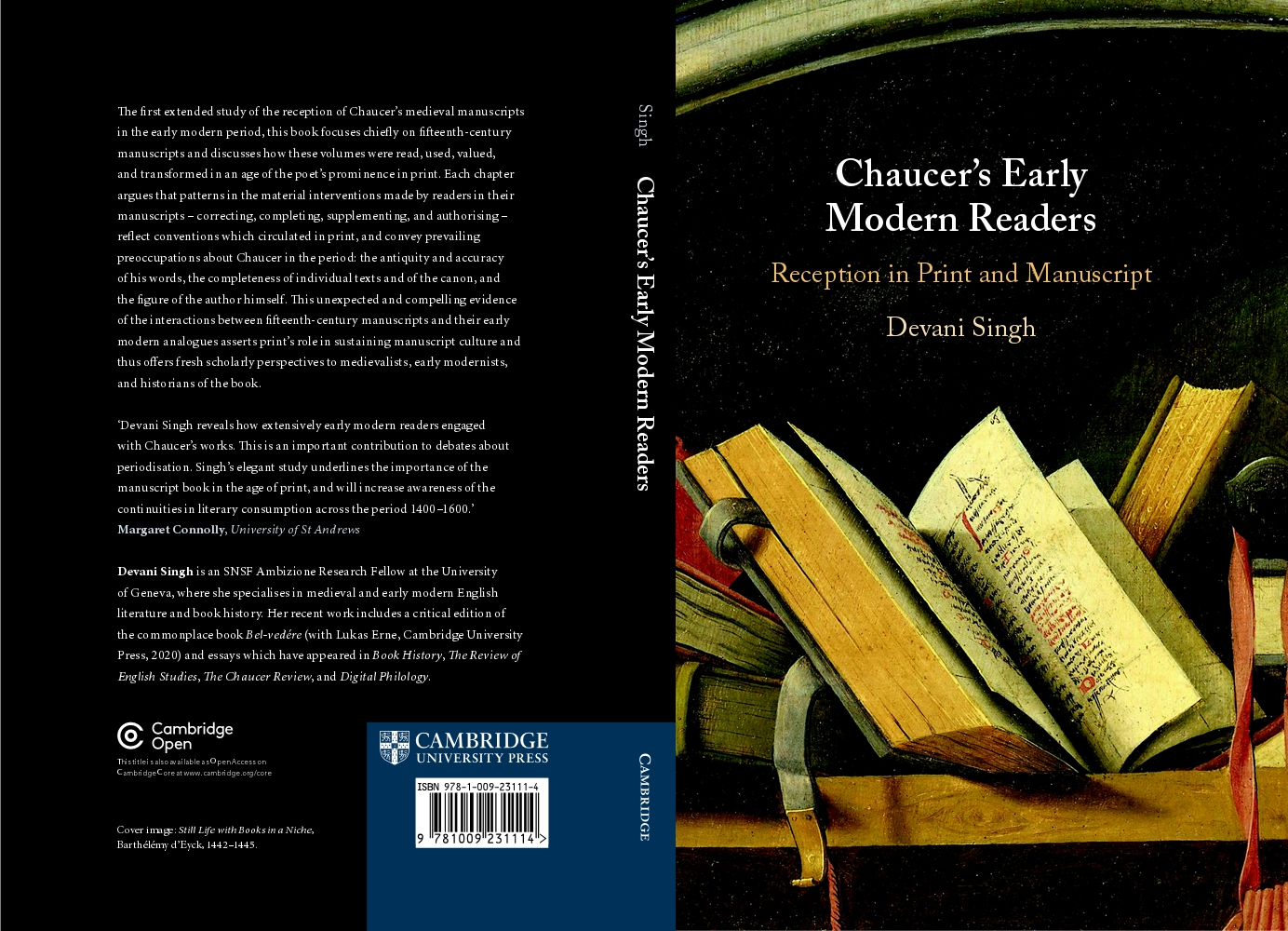

The book, Chaucer’s Early Modern Readers: Reception in Print and Manuscript, by Gates Cambridge Scholar Devani Singh [2011] is an exploration of 15th-century manuscripts and discusses how these volumes were read, used, valued and transformed in the move to print. It argues that patterns in the material interventions made by readers in their manuscripts – correcting, completing, supplementing and authorising – reflect conventions which circulated in print and convey prevailing preoccupations about Chaucer in the later period. It challenges the boundaries of medieval and early modern periodisation by paying close attention to details of book production and reception from the 15th century and into the 18th, drawing on a wide range of annotations, marginalia, supply leaves, portraits and bindings found in dozens of surviving copies of Chaucer manuscripts and printed books.

Published by Cambridge University Press, the book – a history of reading in the early modern period – is an offshoot of Devani’s PhD on Chaucer’s early modern reception in print.

An object that travels through time

Devani says she had been thinking about Chaucer and the idea for the book since she was an undergraduate at the University of Toronto when she worked for a year as a research assistant for Professor Alexandra Gillespie, a book historian and Chaucer specialist. Professor Gillespie brought her to Cambridge on a research trip and planted the seeds for continuing her studies in such a historic setting. Devani did her master’s at Trinity College, Oxford where she learned how to date and analyse manuscripts and then moved to Cambridge for her PhD where her focus was on print. “Through this period I started to understand the book as an object that travels through time,” she says.

She says Chaucer was very interested in his own afterlife. He even wrote a poem sharing his wish that scribes would copy his works in a way that was true to what he wrote. But he was also sensitive to the capacity for language and texts to change over time, and contributed to this change by reworking and adapting earlier texts written by others. “He was deeply aware that language and literature are not static and I think he would appreciate that change was the way for his works to survive.”

Her book seeks to trace what happened to them in the period after his death, about a century before Caxton began printing books. Devani argues that her findings are relevant today as we move from print books to digital ones, with the way we engage with digital books strengthening the appeal of traditional books. “The same complex crossover was happening with newly printed books,” she says. There were additions such as glossaries and a portrait of the author, but the printed versions didn’t replace the originals. People read them side by side. “The new books became a way to extend the life of the old books. They were revitalised by new technology,” says Devani. “It is not that the new just replaced the old. Culture works in more complicated ways.”

One example is a medieval manuscript of the Canterbury Tales at the Bodleian Library (MS Laud. Misc. 739) which saw a series of more than 450 corrections and glosses added by two anonymous 17th-century readers. They painstakingly compared the 15th century manuscript against an early printed copy of the book with the aim of improving the text of the older book. Devani says: “This runs somewhat counter to the natural assumption that antiquarian readers would trust older texts over newer ones, but the readers’ corrections show that they invested the newer printed version with a greater textual authority than the medieval manuscript.”

Flexibility

She says her book, which is unusual in its focus on one author in particular, adds to a growing body of books on manuscripts and how they interact with the print world. “This type of work is having a bit of a moment,” she states. It reminds readers today that Chaucer has always been subject being reinvented for new purposes. “The Canterbury Tales are more mobile than we realise. It’s now generally seen as a canonical and stable collection, but some of the tales circulated with other works and without the author’s name, outside of the pilgrimage frame narrative invented by Chaucer, while some works not by Chaucer at all masqueraded as part of the Tales,” she says, adding that other changes include alterations made by scribes when they rewrote the text according to their own regional English dialects.

“There is an extreme amount of flexibility and changeability in the material record. There is a more dynamic textual tradition than the general reader is aware of,” she states. Ideas about the author changed over time too, for instance, although he lived before the reformation and was therefore a Catholic, later readers from the Protest movement claimed him as one of their own as he was sympathetic to religious reform. “He was co-opted and rehabilitated in Protestant garb for the Protestant age and in that way was made relevant to that age,” says Devani.

Her book studies how readers reconciled the multiple versions of Chaucer they encountered in medieval manuscripts and newer printed books. IT concludes that not only did the new medium of print not hasten the obsolescence of older Chaucer manuscripts, but instead extended their longevity by inspiring readers to transform and perfect them.

The history of prologues

Devani is currently leading another project on literary history at the University of Geneva, studying the history of prologues and prefaces which started to appear in print in the late 15th century.

She says being at Cambridge as a Gates Cambridge Scholar, where was involved in the Medieval Reading Group and its associated journal, “Marginalia”, was a very important period for her. “My Cambridge PhD rounded out my training as a book historian of the middle ages and Renaissance and that would not have been possible without Gates Cambridge,” she says.

Devani, who served as Chair of the Gates Cambridge Scholars’ Council (2013-14), says she really benefited from her time in the Gates Cambridge community. “You are surrounded by so many inspiring people in the Gates Cambridge world that you cannot help but absorb some of the passion that seems always to be in the air. This has all kinds of intangible benefits, but one concrete one is that I had the chance to discuss my ideas at length with many other scholars, most of whom worked outside the field of English literature, and to learn from them in turn. This ability to communicate to interested non-specialists what your work contributes to society and why it matters is a vital skill, perhaps especially for those of us in the humanities,” she says.

She continues to benefit from the network she built at Cambridge, having recently been invited back to a seminar in the English Faculty to talk about her book. “I hope it will inspire others to talk about questions regarding the reception of middle England authors in the early modern period. Scholars increasingly speak about the medieval and the early modern as a period of historical continuity rather than rupture, but there is still much work that remains to be done. Old books and old stories from the Middle Ages were still very much in circulation when poets like Shakespeare and Dryden were writing, and my book follows the older books into the era of these later authors.”

*Chaucer’s Early Modern Readers: Reception in Print and Manuscript is published by Cambridge University Press. The title is also freely available in open Open Access.