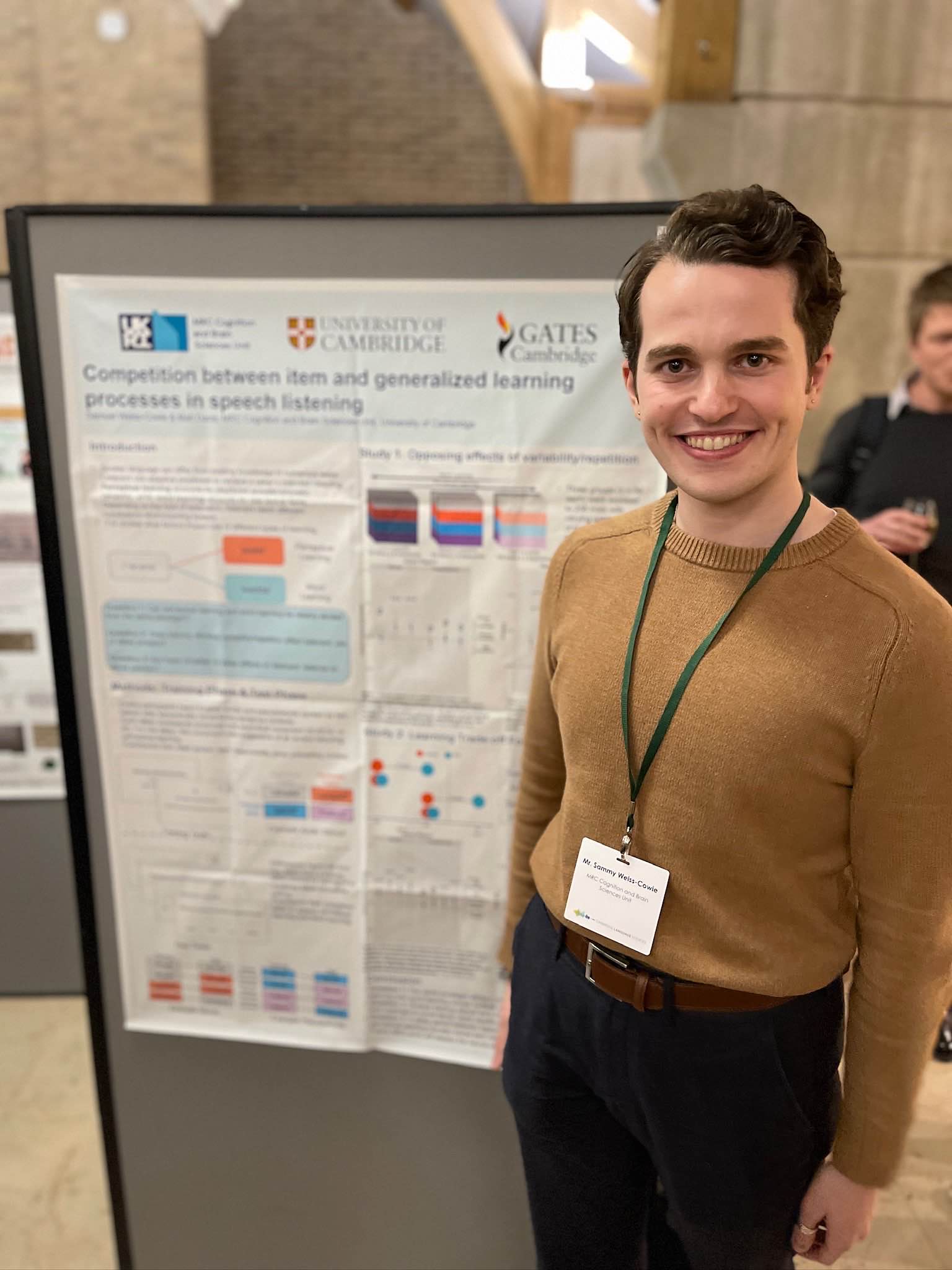

Samuel Weiss-Cowie talks about his research into how the brain learns a new language or new words in a native language.

By discovering what scenarios allow for optimal word learning, I hope to inform more effective methods in language pedagogy.

Samuel Weiss-Cowie

Samuel Weiss-Cowie’s fascination with language learning began at the age of 15 when he started learning Korean. He is now in the third year of his PhD looking at how the brain learns a new language or new words in a native language.

He says: “I wanted to see what was happening in the brain to make this process easier. My interest is in natural ways of learning and how we figure out what the meaning is based on the context.” Most of his research has involved people learning new words in their native language and he would ideally like to focus on new language learners. He uses behavioural methods from Psychology and neuroimaging so that he can see how learning occurs in real time and how people become attuned to two separate learning processes, the cognitive process of learning how to use new words and the more perceptual process of understanding different accents. One experiment involved putting nonsense words into sentences to see if speakers could work out how to use them from the context in which they were used.

Through investigating the neural underpinnings of speech perception, Samuel says his goal is to research the ways in which our brains deal with ambiguous speech. He states: “As anyone who has learned a new language will attest, it can be exceptionally difficult to identify the words produced by native speakers. Myriad factors – such as a loud environment, accented speech, or unfamiliar vocabulary – can also make fulfilling one’s role as a listener more difficult, even in one’s native language. By discovering what scenarios allow for optimal word learning, I hope to inform more effective methods in language pedagogy.”

Learning languages

Samuel [2022] was born and grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, in a family of English literature aficionados. His parents studied English literature and both retired early, although his father later went back to university to do a PhD in English literature in his 50s, remotely, at the University of Birmingham’s Shakespeare Institute when Samuel was in high school. He is now a professor. His mother, meanwhile, has started a jewellery business. “They made me feel I could do whatever I wanted to do and that I did not have to be tied to one possibility,” he says, adding that his father’s experience also introduced him to the idea of doing a PhD.

Samuel went to a private Jewish school until 12th grade. It was mostly secular, but he learned Hebrew and describes himself as very studious. In his teens, he gravitated towards English and History. At around 15, he started learning Korean after being introduced to a Korean pop group and would listen to Korean language lessons as he was driving to school and take Flash cards with him everywhere.

His interest in Korean music quickly developed into a passion for the Korean language. “I was very committed. It was a real passion. I listened to podcasts and tv shows and later read Korean literature. It felt like the language was very intuitive, much more so than my language courses in school. It also had an alphabet, Hangul, which was specifically designed to be easy to learn,” he says. Samuel had just started studying Psychology at the time and soon became interested in what is going on psychologically when we seek to acquire a new language and what makes some languages easier to learn than others. “It was fortuitous that these two interests came together about the same time,” he says. He decided to bring the two together at university.

Undergraduate studies

Samuel did a dual major at Georgia Institute of Technology, starting in 2018. The year before he started a new course on neuroscience had begun and in his first year a programme on Korean was added which his cohort helped to shape. After his first year, Samuel spent two months in the summer in Seoul at Yonsei University, doing an intensive course in Korean language. “It made it all more real as I could talk to people in Korean and it pushed me to use the language every day,” he says. He started reading Korean literature and found the experience of engaging with the story in a different language ‘magical’ and says it made him feel closer to the author.

The final part of his undergraduate course took place during the first part of the Covid pandemic and Samuel took extra classes so that he could graduate earlier. That meant that between finishing and starting his PhD at Cambridge in 2022 he was able to travel around Korea. He says he had hoped to take part in undergraduate research studies on neurolinguistics or psycholinguistics, but Georgia Tech did not have experts in this field. So instead he did two separate studies in neuroscience and linguistics. His professor in the Korean department, Dr Seung-eun Chang, was a phonetician who was working on the pronunciation patterns of heritage learners such as Korean Americans. Samuel attended his first research conference with her. At the same time Samuel was working with Dr Audrey Duarte in a neuroscience lab, studying how depression affects memory. He says both academics were excellent mentors to him.

Cambridge

For his PhD he was able to bring both strands of his research together at the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit under Dr Matt Davis. Samuel is still collecting data and is working on a paper looking at the role of sleep in different types of learning. On the side of his studies, he teaches undergraduate Korean students English and helps prepare Japanese high school students from English language programmes in Cambridge. He spent last summer in Japan teaching English to Japanese students and says teaching as well as studying language learning in the lab gives his research an extra dimension. Samuel has also been involved with the Aurora NK tutoring programme which connects people who have defected from North Korea with English language tutors to build their language skills and aid their integration.

For his PhD he was able to bring both strands of his research together at the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit under Dr Matt Davis. Samuel is still collecting data and is working on a paper looking at the role of sleep in different types of learning. On the side of his studies, he teaches undergraduate Korean students English and helps prepare Japanese high school students from English language programmes in Cambridge. He spent last summer in Japan teaching English to Japanese students and says teaching as well as studying language learning in the lab gives his research an extra dimension. Samuel has also been involved with the Aurora NK tutoring programme which connects people who have defected from North Korea with English language tutors to build their language skills and aid their integration.

He says: “I hope my work can help identify more optimal ways to learn languages or deal with issues people may have with their native languages. I have had such a positive experience of learning languages, but so many people think it is challenging to learn a language. If I can make it easier then that would be fantastic.”