Daniel Hanigan and Grant Kynaston solve a textual problem in an ancient manuscript that has troubled scholars for over 400 years

Our finding now allows future students and scholars to read this crucial witness to ancient history and geography on its own terms.

Two Gates Cambridge Scholars have joined forces to correct a mistake that has persisted in classical scholarship for over 400 years.

Daniel Hanigan [2019] and Grant Kynaston [2019] have just published Autopsy and didactic authority: rethinking the prologue of the Periodos to Nicomedes, an article in Classical Quarterly, the leading journal in Classical Studies, in which they solve a textual problem in an ancient manuscript that has troubled scholars for over 400 years.

The Periodos to Nicomedes is a Greek poem from the second century B.C.E. which is attributed to an anonymous author conventionally referred to as Pseudo-Scymnus. It constitutes a poetic circuit of world geography.

The text is an example of patronal poetry and is thought to have been presented as a gift to King Nicomedes III Euergetes of Bithynia who financed its composition. Nicomedes was a minor Hellenistic monarch who wanted to rule the world. By gifting Nicomedes the Periodos, Pseudo-Scymnus was offering his patron a microcosm of a world that he was never actually able to conquer.

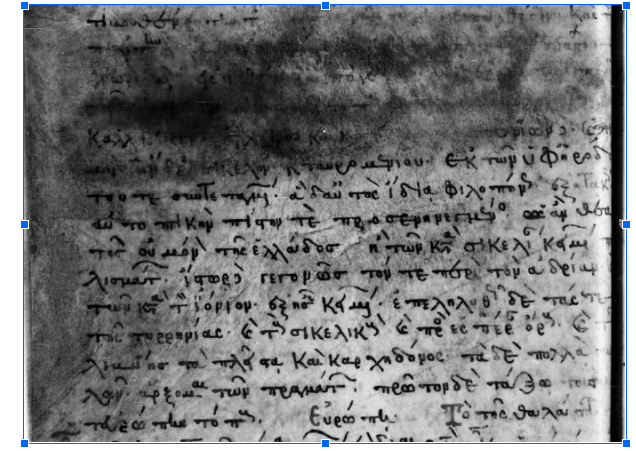

The text survives, but in a state of disrepair. The poem is preserved on a single manuscript, dating to the late 13th century. However, while the first half covering the coastlines of Spain, Liguria and the Black Sea survives, although there is considerable damage at a key point in the text, the second half, covering Africa and Asia, was at some point detached from the manuscript, and survives only as fragmentary quotations in the sixth century Periplous of the Euxine Sea attributed to Pseudo-Arrian.

The damaged part of the Europe section is the prologue of the Periodos, in which Pseudo-Scymnus explains the rationale for its composition and offers a list of sources he consulted while writing. In the midst of the catalogue of ancient historians, the ink has smudged, completely obscuring the text.

The readable section recommences with an enigmatic reference to Timaeus of Tauromenium, the well-known Hellenistic historian of Western Greece, and his better-known predecessor, Herodotus. This is followed by what critics since David Höschel in 1600 have assumed to be a contrasting account of Pseudo-Scymnus’ own travels through Western and mainland Greece.

The readable section recommences with an enigmatic reference to Timaeus of Tauromenium, the well-known Hellenistic historian of Western Greece, and his better-known predecessor, Herodotus. This is followed by what critics since David Höschel in 1600 have assumed to be a contrasting account of Pseudo-Scymnus’ own travels through Western and mainland Greece.

However, the researchers point out that there is no textual reason for assuming that the traveller described in this section is Pseudo-Scymnus himself. Moreover, Pseudo-Scymnus makes clear at multiple points in the poem that he has derived his material from existing prose sources rather than travelling the globe and recording his personal observations. They say these problems are compounded by the fact that the relevant section of text is nonsensical at this point: the lines about Herodotus and Timaeus do not cohere, either with each other or with the following passage.

In the article, Hanigan and Kynaston, who both did their undergraduate studies at Sydney University and won the Gates Cambridge Scholarship in the same year, show that the passage actually refers to Timaeus, and that the confusion has arisen, not because of the smudged ink, but because a single line was omitted by the scribe who copied the text before it was damaged. They reconstruct the lost line of text, restoring sense to the passage and making clear that Timaeus is the true subject of the section.

They say their discovery provokes a re-interpretation of the Periodos that recognises the text as a work of pure Hellenistic book-learning, not a hybrid of scholarship and exploration, as previous critics have suggested. It also prompts new consideration of the dynamics of Hellenistic historiography by suggesting a new appreciation of Timaeus.

Hanigan and Kynaston say the work would not have been possible without drawing together multiple skillsets from Classical scholarship: literary interpretation, historical contextua lisation, linguistic analysis, textual criticism and the digital humanities.

They say: “This finding now allows future students and scholars to read this crucial witness to ancient history and geography on its own terms.”

*Picture credit: A City of Ancient Greece. With the return of a victorious armament by William Linton (1791–1876) courtesy of Wikimedia commons.