Andrés Alfonso-Rojas on his passion for tracing the origins of snake diversity in South America

The fossil anacondas [I am studying] were around the same size as the big green anaconda we see today, and they still seem to be thriving although their ecosystem has changed and many other animals in that ecosystem have disappeared. Why?

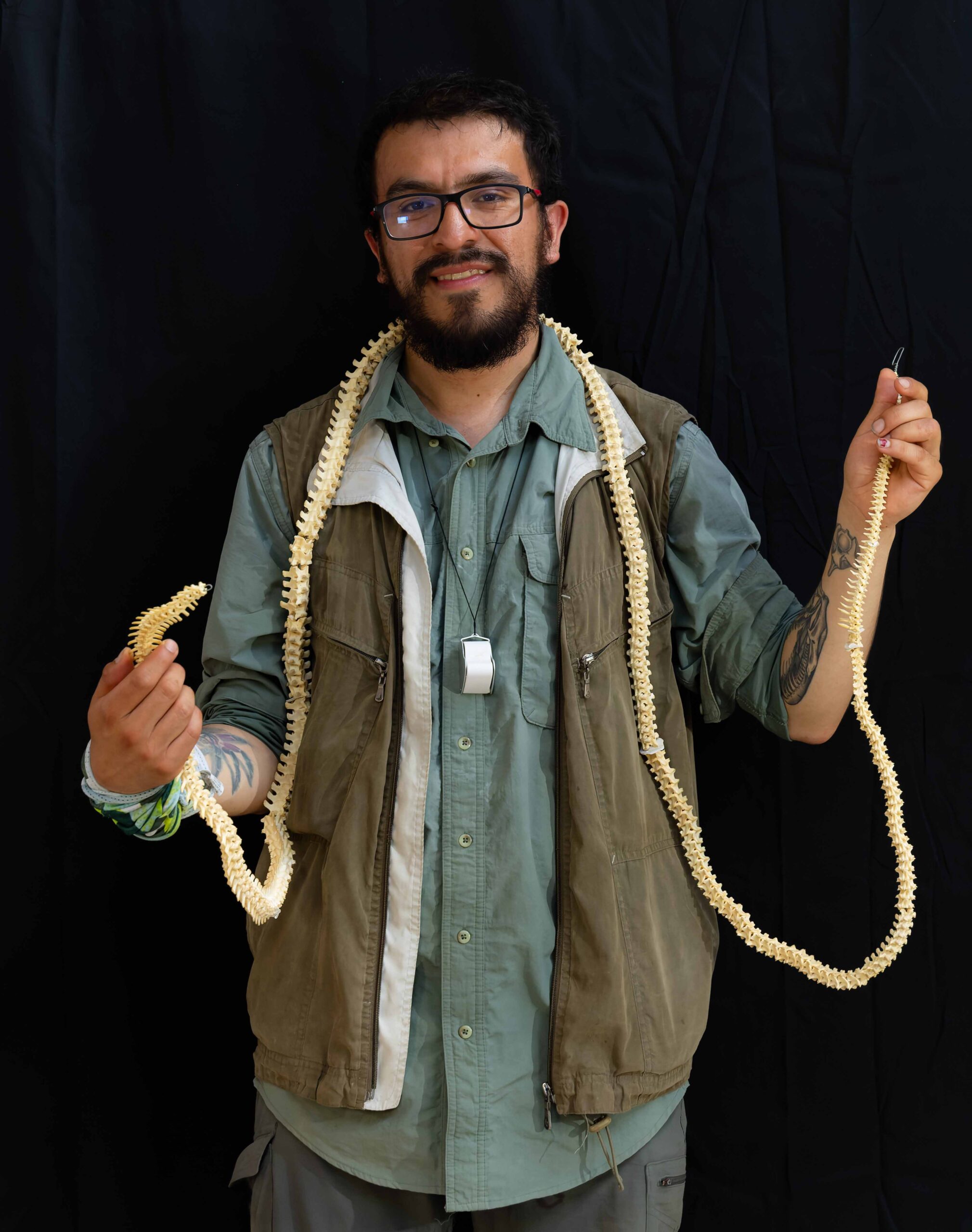

Andrés Alfonso-Rojas

“Snakes to me are the most beautiful creatures that exist. They look so simple, but they are so complex. They can glide, swim and burrow. They are so varied. I want people to see how amazing and beautiful snakes are,” says Andrés Alfonso-Rojas [2022].

His love of snakes has fuelled his PhD in Zoology. Andrés is using fossils and molecular data to study the diversification of snakes, especially colubroids, in the Neotropics.

Colombia was home to one of the largest snakes that ever existed, Titanoboa, which dates back to around 64 million years ago when South America was an isolated land mass. That giant snake, which was related to today’s boa constrictors and anacondas, inspired Andrés to investigate the evolution of snakes in South America, given that the fossil record is quite patchy.

Colombia was home to one of the largest snakes that ever existed, Titanoboa, which dates back to around 64 million years ago when South America was an isolated land mass. That giant snake, which was related to today’s boa constrictors and anacondas, inspired Andrés to investigate the evolution of snakes in South America, given that the fossil record is quite patchy.

There is a big fossil gap between these giant snakes and smaller and more diverse colubroids, the group that includes vipers, coral snakes, vine snakes, racers and many other snakes commonly found nowadays. Andrés says it is inferred that these smaller snakes came from elsewhere, probably North America. They could have swum or jumped from island to island, before the closing of the Panama isthmus, but no-one yet knows why that might have happened.

Andrés’ work involves the use of molecular phylogenies (dendrograms like family trees) and ecological traits of modern snakes, such as what prey the snakes ate and whether they lived in trees or on the ground, to reconstruct the ancestral ecology of early South American snakes. “I am trying to reconstruct what happened to the ancestors of different types of snakes using a probabilistic model linked to climate and geological events,” he says. He has also been looking at giant snake fossils which are related to modern anacondas. He developed a model to predict their body size and says there seems to have been little change over the last 15 million years based on fossil finds.

“These fossil anacondas were around the same size as the big green anaconda we see today, and they still seem to be thriving although their ecosystem has changed and many other animals in that ecosystem have disappeared. Why? One hypothesis is that they are aquatic and generalist faunivores and eat lots of different animals from fish to turtles and medium-sized mammals, so considering that most of these preys are still present, they have not needed to change,” says Andrés.

Civil engineering

Andrés’ life could have gone down a very different path, however, although he had a passion for wildlife from an early age. Born and raised in a big house in Bogota, Colombia, he lived with his mother and grandmother and at one point his aunt and five cousins shared the house. Andrés says they were like siblings to him. He also has a half-brother. His father was an electrical engineer and business manager and his mother was a primary and nursery teacher. When they split up it was agreed that his mother would take care of his schooling while his father would be in charge of his university studies.

As a young boy, Andrés attended private schools, but says he didn’t feel comfortable among his more privileged classmates. His uncle was working at a secondary school which the school’s principal had opened to less affluent children. The principal also emphasised the importance of reading and in the mornings the entire school would start the day with a reading session. And he encouraged students to travel and explore the world. Andrés learned English and music, joining an orchestra to play the violin, and took up graphical design. For the first time he started forming friendships. He did well academically, particularly at Maths, Science and History.

Although Andrés had a long fascination with fossils, wildlife and dinosaurs, with a family full of engineers there was strong pressure to follow the family tradition and concern that studying fossils wouldn’t lead to a steady job. So Andrés went straight to university and started a Civil Engineering course. His father had saved money so he was able to attend the same private university he had studied at – the Universidad de Los Andes in Bogota. Andrés got a scholarship due to his performance in the national high school exit examination to fund his early studies, but he didn’t enjoy the course and missed lots of classes.

Fortunately, he was able to take classes in other subjects alongside his Engineering course and so he started studying Biology. “It was like a spark had ignited in me,” he says, adding that he was constantly asking questions in lectures. He was able to take the course as a minor subject and he benefited from an excellent professor, Dr Emilio Realpe, who told him he could continue to attend classes and do exams when his course was over. During the summer break before his final year the professor called him and asked him why he wasn’t studying Biology instead of Civil Engineering where he was failing several classes.

Paleontology

Andrés felt he couldn’t let his father down by pulling out of Civil Engineering, but the professor convinced him that he could do both courses. It took Andrés eight years to graduate and a lot of hard work. He graduated from Civil Engineering in 2017 and from Biology the following year. In the summer in between Andrés had the opportunity to do an internship in the US. He chose the University of Washington in Seattle due to its research in Paleontology, but due to his low grades in Civil Engineering he thought he wouldn’t be accepted. He was and took part in a field trip to Montana, digging up dinosaur fossils including a T-rex skull.

Andrés felt he couldn’t let his father down by pulling out of Civil Engineering, but the professor convinced him that he could do both courses. It took Andrés eight years to graduate and a lot of hard work. He graduated from Civil Engineering in 2017 and from Biology the following year. In the summer in between Andrés had the opportunity to do an internship in the US. He chose the University of Washington in Seattle due to its research in Paleontology, but due to his low grades in Civil Engineering he thought he wouldn’t be accepted. He was and took part in a field trip to Montana, digging up dinosaur fossils including a T-rex skull.

“I wanted to learn about everything. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, a dream for me,” he says. On his return after two months in the US, Andrés started looking for jobs. There was nothing in Biology and so he took a Civil Engineering role. He was allowed one week off to attend a Paleontology conference and discovered there were many Colombian paleontologists. “It was like a revelation for me,” he says. He started doing some volunteer lab research, but had to give that up when his Civil Engineering role ramped up. A year later a Colombian paleontologist, Dr Edwin Cadena, contacted him and offered him a research assistant role. It was 2019. Andrés quit his engineering job and focused 100% on Paleontology.

Postgraduate studies

The next step for him was to do a master’s and PhD and he wanted to study overseas, but his average grades from the Universidad de los Andes made it difficult for him to study abroad. He applied for a master’s in Colombia and started studying Colombian fossils at the Universidad del Rosario in 2020 with the aid of a scholarship. He became interested during his undergraduate studies, but it was only after contracting Covid and being forced to stay at home that he started doing research on them. He read lots of books on snakes and started assembling the skeleton of a Boa constrictor gifted by a colleague.

Andrés had never considered applying to the University of Cambridge, but he visited the University of Florida, took notes on fossils of giant snakes that he was not supposed to see and came into contact with his current supervisor, Professor Jason Head. Professor Head suggested he apply to Cambridge. He had very little time to put together his PhD proposal on how snakes became so diverse in South America, but he was successful.

Andrés started his PhD in 2022 and has done field work in Colombia and Peru. He has also begun to collaborate with several colleagues from Venezuela, Bolivia and Panama. He has already finished his first paper on his PhD, having contributed to four before he arrived at Cambridge; he is writing a review of a book on the evolution of snakes; and he has been reviewing papers for different academical journals, as well as presenting at conferences. Additionally, as part of his PhD, he is describing several fossils of snakes, including the oldest colubrid known for South America and a new species of snake which fossil record extends from Bolivia to Venezuela. When he has completed his PhD, Andrés wants to keep working on South American fossils and to mentor students.

Andrés started his PhD in 2022 and has done field work in Colombia and Peru. He has also begun to collaborate with several colleagues from Venezuela, Bolivia and Panama. He has already finished his first paper on his PhD, having contributed to four before he arrived at Cambridge; he is writing a review of a book on the evolution of snakes; and he has been reviewing papers for different academical journals, as well as presenting at conferences. Additionally, as part of his PhD, he is describing several fossils of snakes, including the oldest colubrid known for South America and a new species of snake which fossil record extends from Bolivia to Venezuela. When he has completed his PhD, Andrés wants to keep working on South American fossils and to mentor students.

Despite a lack of investment in Paleontology in his native country, interest is beginning to build, he says. A Paleontology museum has been built in the small village of La Victoria which is attracting more and more visitors. Andrés is also doing his bit to build interest. In the past he has worked at summer camps for children in Colombia. Every time he returns to Colombia he also visits his old school and gives talks. And he drops in on the Biology professor who helped set him on the path to what he is doing now.

Recognising that his career could have taken a very different route, he says: “I feel very grateful to them. It is important to show gratitude and acknowledge the people who encouraged and supported me to follow my dreams.”