Julien Domercq talks about his experience curating a Degas exhibition at the National Gallery and his research into changing depictions of the Pacific.

Julien Domercq has just finished his first job curating an exhibition. The Drawn in Colour: Degas from the Burrell exhibition at the National Gallery has won five-star reviews from the critics and been seen by just under 400,000 visitors.

Julien [2013] took on the curating role just over a year after taking time out from his PhD to take up a two-year entry-level contract at the National Gallery.

He had just eight months to bring the exhibition together. He says: "One morning in our shared office overlooking Trafalgar Square, Christopher Riopelle, the Curator of Post-1800 Paintings at the Gallery, turned towards me and said, casually: 'Would you like to curate an exhibition on Degas?' 'Let me think. Yes!' came my reply. It was such a unique, generous gift from someone who has been such an inspiration and a supporter of my work here at the National Gallery." It was a huge opportunity, but a very tight timetable. Julien had to decide what the show would be about and what works to display. He also had to write the catalogue.

He helped to convince the Burrell Collection in Glasgow to lend 20 of their 22 Degas works for the exhibition. Many were fragile pastels. Julien had to work with a panel of experts to determine which ones could be transported and how this could be achieved safely. This involved designing new crates and establishing a new transport protocol.

Julien also sourced some other Degas works and combined them with other pictures by the artist in the National Gallery’s collection to create a coherent narrative. “The extraordinary loan from the Burrell was the backbone of the exhibition,” he says. “It had a three-part thematic structure. We used the other works to reinforce the themes, creating meaningful juxtapositions which related the works by theme rather than by date. The aim was to show Degas as a painter who experimented across media, and across time too.”

He was very pleased with the response. “People loved that it was a relatively small exhibition which allowed the pictures to breathe,” he says. “I wanted it to be an aesthetic experience and to let the works shine. People got quality time up close with the works.”

Julien is passionate about making art more accessible and not only was the exhibition free, but he wrote the introductory essay in the catalogue, aiming to distil Degas’s life and work into an account which would have a broad appeal.

An artistic family

A love of art runs deep in Julien’s family. “My mother is convinced (and she’s probably right) that taking me to exhibitions as a six month old set me up for what I am doing now,” he says.

Born in Paris, Julien went to a Montessori school where he could decide what he wanted to do – which was to draw all day long. In Geneva, where his family moved when he was six, his school had children from 120 different nationalities and claims to be the first international school founded by the League of Nations. “It really was a melting pot. It was an eye-opening experience. I felt truly like a global citizen. I lived and breathed global citizenship,” says Julien.

At school, he followed a studio-based arts programme, was passionate about history, did a lot of theatre, ran the film club which showed world cinema and was involved in student governance. At the time he wanted to be a film maker and wrote to film director, producer and screenwriter James Ivory at the age of 16 to say how much he loved his films and how he wanted to work in the industry. Within six months he met James Ivory on a trip to Geneva. “It was a wonderful meeting of minds,” says Julien. Ivory became a mentor figure to Julien and the two kept in touch through postcards in which they discussed history and ideas.

Julien was not certain what to study at university and was torn between film and art history after attending summer schools in London and Cambridge. He also attended an open day at Cambridge where he met his PhD supervisor Professor Jean-Michel Massing and knew that he wanted to study with him.

When he got better results in his exams than he had anticipated, Julien decided to defer going to a university for a year. During his gap year he contacted James Ivory and was hired to work on the film The City of Your Final Destination with Anthony Hopkins and Charlotte Gainsbourg which was shot in Argentina. He had his interview for Cambridge the day before he flew to Buenos Aires.

Julien started his degree in Art History at Cambridge in 2007 and was based at King’s College. Over the course of his degree he was very active outside of his studies. He put together a comprehensive cataloguing system for the King’s College art collection; he re-established a student art collection programme set up by Duncan Grant from the Bloomsbury Group; he represented students on the King’s College governing body; and he was president of the Cambridge Union in 2009, doubling its membership through a drive to make it more inclusive. “It is such a benefit to partake in the Union debates which attract very interesting people. I was uncomfortable that it seemed to have turned into a private members’ club,” says Julien. One way of widening membership involved offering half price membership to students with bursaries.

The struggle to push for greater inclusion left Julien slightly disillusioned about politics and the compromises involved. “I decided to focus on doing something for the common good through something I felt I could truly master,” he said. He threw himself into his dissertation on artistic depictions of the death of Captain James Cook, the British explorer who charted the Pacific Ocean in the second half of the 18th century. “There are dozens of very different versions of Cook’s murder on a beach in Hawaii in 1779. It was an event that no-one witnessed,” he says. “One image [that of John Webber] triumphed and history has been written as if the most popular image was the truth as viewed by an eyewitness. It has become the accepted version of events and has created history.”

He continued his research for his master’s, looking more widely at the depiction of the Pacific in the 18th century and in film in the 20th century when there was a renaissance of interest in the region following Gaugin’s death in 1903.

Film-making

After completing his master’s, Julien moved to London and started working in film, his early desire to be a film maker still lingering. He spent a year and a half working for a small politically engaged production company in Bosnia and the Middle East, covering the Egyptian revolution and helping to administer a film-making prize in Bosnia. The experience showed him how powerful art could be as a force for change, but it also convinced him he was happier watching and talking about films than making them. He missed art history so he applied to Cambridge to do a PhD, seeing it as the gateway to a career in the cultural sector.

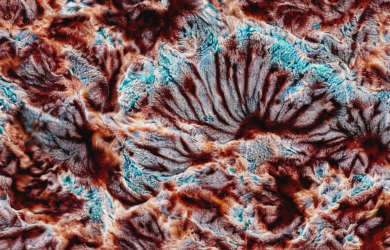

His PhD, for which he was awarded a Gates Cambridge scholarship, focuses on the shift in depictions of the peoples of the Pacific in British and French art from idealisation to demonisation between the Enlightenment and the Age of Empire. “I am interested in the depiction of otherness and the power of images to affect how we understand people we have never met,” says Julien.

As he was coming to write up his PhD the National Gallery contract came up. He applied at the last minute and got the job. It was an offer he couldn’t refuse and Gates Cambridge supported his decision. He had anticipated doing his PhD alongside the role, but found it all-consuming. “Curating requires a tremendous variety of skills,” he says. “No day is the same. The learning curve is quite steep and I had very little time. It is the greatest job in the world, though.”

In his first year he worked on the post-1800 parts of the collection. He helped reorganise the 19th century display of the collection, rehanging the paintings, coming up with a new sequence and hang to explain the pictures and integrating the gallery’s more recent acquisitions within that order. Then in January 2017 came the offer to do the Degas exhibition.

Julien is now keen to finish his PhD and carry on with a job where he has already made a significant impact.

*Picture credit: National Gallery

Julien Domercq

- Alumni

- France

- 2013 PhD History of Art

- King's College

I was born in Paris and completed a BA and MPhil in History of Art at Cambridge. Alongside my academic interests, I served as president of the Cambridge Union, where my proudest achievement was the introduction of half-price memberships for students on bursaries, thus democratising access to the society. After my MPhil, I worked in London for an independent film production company. My PhD proposes to explore how Europeans depicted the peoples of the Pacific in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. When the first explorers returned from the Pacific, its inhabitants were represented as exotic and captivating Rousseauian ‘noble savages’. However, those depictions rapidly changed as the growing European Empires strove to assume racial and cultural superiority over them. These images reveal the dramatic shift from wonder at the Pacific and its peoples to disgust and distrust, from the perception of a noble to that of an ignoble ‘savage’, and ultimately from enlightenment to colonialism. I am currently the Vivmar Curatorial Fellow at the National Gallery in London.