Caroline James plans to research how to bring marginalised voices to the heart of the education system.

If education is to be the great equaliser, it must be tailored, led and informed by the needs, voices, interests and values of the populace it serves.

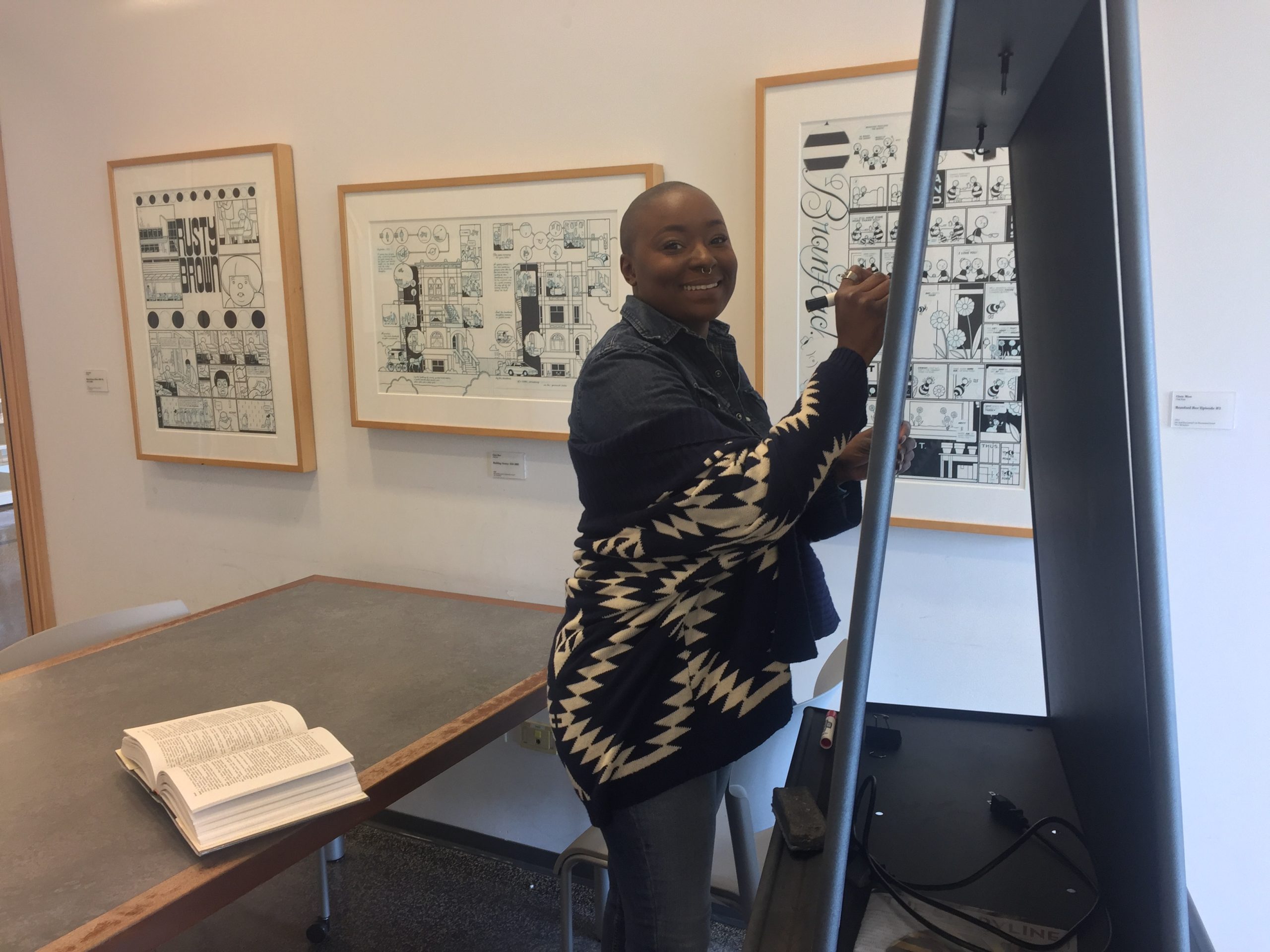

Caroline James

Education has traditionally been seen as a route of poverty, but without structural and curriculum change, says Caroline James, it will only perpetuate existing social inequities.

The Gates Cambridge Scholar-Elect wants to democratise the education system by bringing in the voices of marginalised young people and she plans to start by doing research on foster children.

She has strong personal reasons for doing so since she herself went through the foster system and got her first taste of teaching at a very early age when she stepped into the educator role for her own siblings.

For her MPhil in Education at Cambridge, which she starts in the autumn, Caroline wants to look at how the education system negatively impacts at risk youth, using foster children as a proxy because of her own experience and because research shows consistently that they rank lowest in terms of educational achievement and access to higher education.

“There is such a dearth of research on what foster youth have experienced in education,” says Caroline, who won a national teaching award in the US for her work on curriculum change. “I want to look at this globally and listen to their voices. It’s about getting their voices heard in an effort to democratise education. Education can never lead to greater equality if it just perpetuates social and political inequity and only reflects the dominant community.”

She adds: “I believe that schools that function more democratically are better able to meet the needs and desires of marginalised youth. Such democracy could further translate into improved student behaviour, socio-emotional development and academic outcomes."

Foster care

Caroline [2017] was born in Chicago and her early years were characterised by abuse and neglect. She lived with her father who was addicted to crack and would be gone for weeks at a time. Her mother, who was also a drug user, left when she was two and Caroline only met her again when she was 16. She and her three younger brothers endured periods of homelessness and often missed large chunks of school.

Caroline was like a mother to her brothers, looking after them, giving them food and getting them to school. She got her first taste of teaching as a child when she stepped into the role of educator, making up for the time her brothers missed at school and teaching herself to read so she could teach them. One of her brothers is deaf, but had not been diagnosed which made her job harder and more frustrating.

“As far back as I can remember I thought of myself as a mother to my little brothers. I never experienced being a child,” she says. “It is only three years ago that I spoke to my brothers about learning to be a sister.”

At the age of 10 Caroline decided she needed to work with her teachers to advocate for the family to be taken into foster care. The family moved to Alabama, but it was impossible to find a family who would take all four children. Caroline wanted the boys to stay together so they could support each other. She felt she was more able to fend for herself, but found it hard adapting to being without them. “The role of caretaker and being the responsible one had crafted my character,” she says.

Initially she felt a sense of guilty relief that a weight had been lifted from her and she was able to be her own person. But it was not long before she started to feel lost. There was not much support from the foster system who she felt put too much responsibility on her for making decisions.

In response, Caroline threw herself into the education system. “I felt I had to become someone and not be like my parents. That was all that mattered to me,” she says. “I believed that education would allow me to escape the snares of poverty.”

Neither of her parents had finished high school. Some of her peers in her foster home had a homeschooling arrangement to help them catch up, but Caroline was too far ahead in some areas such as humanities, although she struggled with maths due to being self taught. She was sent to a magnet school, a public school with specialised courses or curricula, and describes it as one of the best schools in Alabama with some of the best teachers. “It allowed me to see myself as an intellectual,” she says. “I wanted to prove that I was smart. Later I was able to question the fallacy that education equalises.

I no longer believe that education is the great equaliser. Our current education systems cannot close the achievement gap, end poverty or enfranchise the disenfranchised. In marginalised communities, education is often simply a reflection of larger systemic inequities; a system that reflects inequities will not create equity. If education is to be the great equaliser, it must be tailored, led and informed by the needs, voices, interests and values of the populace it serves."

Teachers as activists

When she started at the University of Alabama, however, Caroline was set on being a lawyer, not a teacher. “I knew I was an activist and I did a lot of things that gave me a high profile as a leader,” she says, “but I didn’t want to be an educator. I felt insulted. I thought I didn’t do all of this just to end up as a teacher.” However, Teach for America thought differently and they did all they could to recruit her prior to her senior year.

They flew her to New Orleans where she started teaching and began to see education in a new way. “I could see the connection between inequity and education. I began to see teachers as activists. Classrooms were where activism was built because teachers could change lives,” says Caroline. “I could see that the very fabric of our democracy is built in the classroom.”

She began to see the links between her natural desire to be a leader and education. “The unifying thread was social justice,” she says. “I am a product of social injustice.”

She was also able to reflect on the fact that having access to the kind of education provided by the magnet school meant she was privileged in comparison to her peers in the foster home who were going to underfunded public schools where the quality of teaching, resources and expectations were low. At the magnet school she and her fellow students had had some influence over the curriculum, were able to ensure it reflected their lives and talent, meaning they could bring their whole identities to school.

Becoming an educator changed her ideas about what success meant and made her rethink her own approach to education as a way out of poverty. “I changed my orientation – I no longer needed to be better than my parents. I realised that, in some ways, my scorn was misplaced and that, though certainly not blameless, my parents were products of wider systemic issues that needed to be reformed. And I felt a responsibility – because of my experiences – to be part of that reform.”

She felt people who had undergone the kind of life experiences she had had a truth of narrative and identity which could make a difference. “[I felt that our perspective was one which could not be replaced; it’s the perspective of being personally impacted by unjust systems. These perspectives are needed to resolve the issues of inequity]I felt that people like me were who are communities had been waiting for,” she says.

After doing a teacher training programme for Teach for America over the summer, Caroline was thrown in at the deep end and started to teach. “Teaching came naturally to me as I have been teaching for as long as I have been speaking,” says Caroline.

She moved over from teaching to management and managed 60 educators, working on issues such as curriculum change. She won the Sue Lehmann national teaching award from her work to create a curriculum which reflected student culture, interests and identity and tied student leadership with student activism. It was her second award as she was given an undergraduate award for her research into how group perceptions of social issues, such as welfare, affect voting. She says her educational ideology “is about redefining education and changing the power dynamic. I believe we should use the classroom as a space to support marginalised communities in using education, their identities and their inherent leadership as a means to evaluate and dismantle structural and social barriers".

Research

Caroline, who was interviewed about her work for CNN, was keen to extend her research on curriculum change. She spent six months researching programmes around the world, putting them on a spreadsheet. Cambridge was one of three she selected, but she didn’t think she would get in. She states: “I was interested in how the Faculty of Education was looking at leadership in the classroom and tying it to a shift in power dynamics for at risk youth."

She says she is honoured to have been selected as a Gates Cambridge Scholar and hopes that being in a diverse network of scholars working on global issues will lead to interesting collaborations.

Caroline James

- Alumni

- United States

- 2017 MPhil Education (Thematic Route)

- Christ's College

In undergraduate, I was profiled by CNN; this interview gave me the courage to speak with conviction about my identity and how it relates to my work. I am a foster youth. I am a black woman. I am first-generation. I come to Cambridge not only as an educator but as an activist focused on improving life outcomes for marginalized youth. In New Orleans, LA, I had the privilege to teach. I learned that leading requires learning from those whom you lead. My principal, my students and the community I served, all shaped my perception of education. Together, we developed academic curriculums that reflected student culture, interests and identity. Furthermore, we created an incredible approach to student leadership development. As a result, I won Sue Lehmann, a national teaching award. After leaving the classroom, I moved into teacher leadership development. Through Teach For America, I had the privilege to partner with and manage almost 60 educators. At Cambridge, I will explore research-based methods to democratize education. I believe that schools that function more democratically are better apt to meet the needs and desires of marginalized youth. Such democracy could further translate into improved student behavior, socio-emotional development, and academic outcomes. Words cannot explain how honored I am to join the Gates Cambridge community of passionate learners and ethical leaders.

Previous Education

The University of Alabama