Nick Posegay's latest study focused on the late texts from the Cairo Genizah which may shed new light on the late Ottoman era

Altogether, these texts show a complex literary landscape in this community, one which drew materials in many languages from around the Mediterranean basin.

Nick Posegay

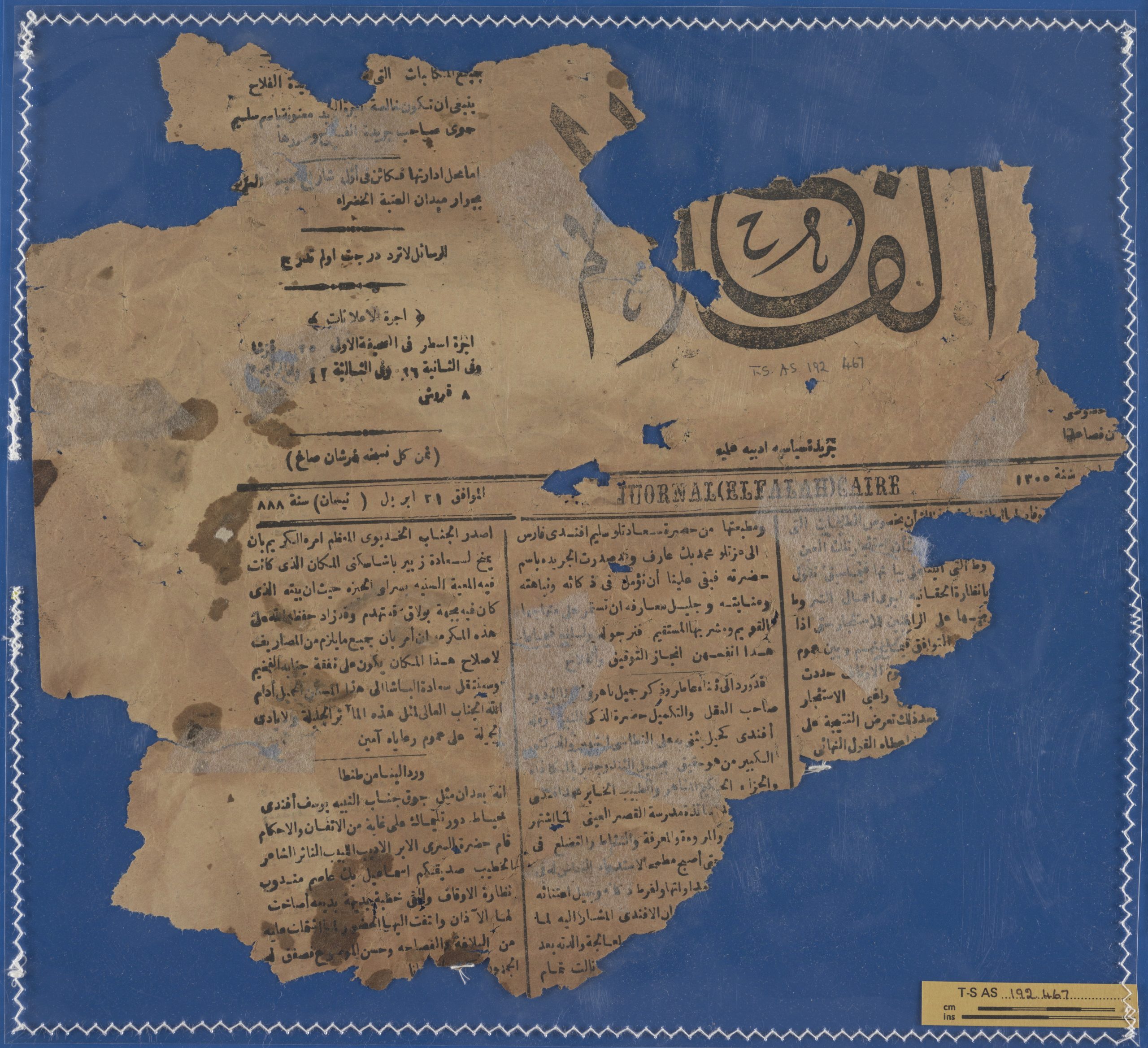

The Cairo Genizah – a repository of hundreds of thousands of manuscripts that the Jewish residents of Old Cairo produced and consumed in the pre-modern period – also contains hundreds of texts from as late as the 19th century, some of which hold important information about the late Ottoman era, according to a new study.

The study, by Nick Posegay [2017], published in the International Journal of Middle East Studies, looks at the later Cairo Genizah texts found in a Cairo synagogue, most of which were brought to the Cambridge University Library in 1897 under the auspices of Solomon Schechter, former Reader in Rabbinics. A ‘genizah’ is a hidden space meant to store sacred texts that are too old or damaged for further use.

While more ancient Cairo Genizah texts have been studied by many scholars, with foreign “collectors” having acquired most for European libraries in the second half of the 19th century, the later documents are less well known.

Posegay’s article notes how the Cairo Genizah is a remarkable resource for tracing Middle Eastern history between the seventh and nineteenth centuries, but that many of its manuscripts from the second half of the 19th century remain unidentified and understudied.

They include texts directly related to marriage and divorce customs, the history of Middle Eastern printing, Jewish migration patterns, book trade between Europe and Egypt and the lives of prominent members of the Egyptian Jewish community. Posegay, who did his PhD in Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, funded by a Gates Cambridge Scholarship, says: “Altogether, they show a complex literary landscape in this community, one which drew materials in many languages from around the Mediterranean basin.”

Implications for Ottoman history

He points out that, unlike earlier Genizah material, any manuscript or printed text produced after 1864 would also have been affected by the influence of European scholars as collectors and representatives of foreign universities sought to purchase Egyptian manuscripts for European libraries. Posegay says this financial incentive may explain why certain late items, such as Arabic newspapers and textbooks, wound up in Genizah collections despite having no clear reasons to be stored there.

He states: “There is no doubt that most of these late fragments are artifacts of late Ottoman Cairo, but we cannot be sure that anyone stored (or intended to store) them in a genizah.”

He believes, however, that these fragments should be examined in the study of both Ottoman and Jewish history. He is calling on institutions that hold late Genizah material to devote resources to the cataloguing and description of late items, including a large number of neglected printed books. He states that such cataloguing will require assistance from bibliographers and specialists in post-medieval languages, including Ladino and Modern Arabic, among others.

He argues that such data will make it possible for scholars to compare subsets of late fragments with library acquisition records, potentially enabling archivists to detect correlations between manuscript subcollections and the activities of known Genizah collectors. The data can also be used by Ottomanists, Arabists and European book historians to conduct more targeted studies of late Genizah material and shed new light on the history of nineteenth century Cairo.

Posegay says this will require cooperation from scholars of many related fields, adding: “The late dated items surveyed here – as well as hundreds more undated fragments – merit further investigation that may yet illuminate the history of late Ottoman Egypt.”

Picture credit: T-S AS 192.467, courtesy of the Syndics of the Cambridge University Library.