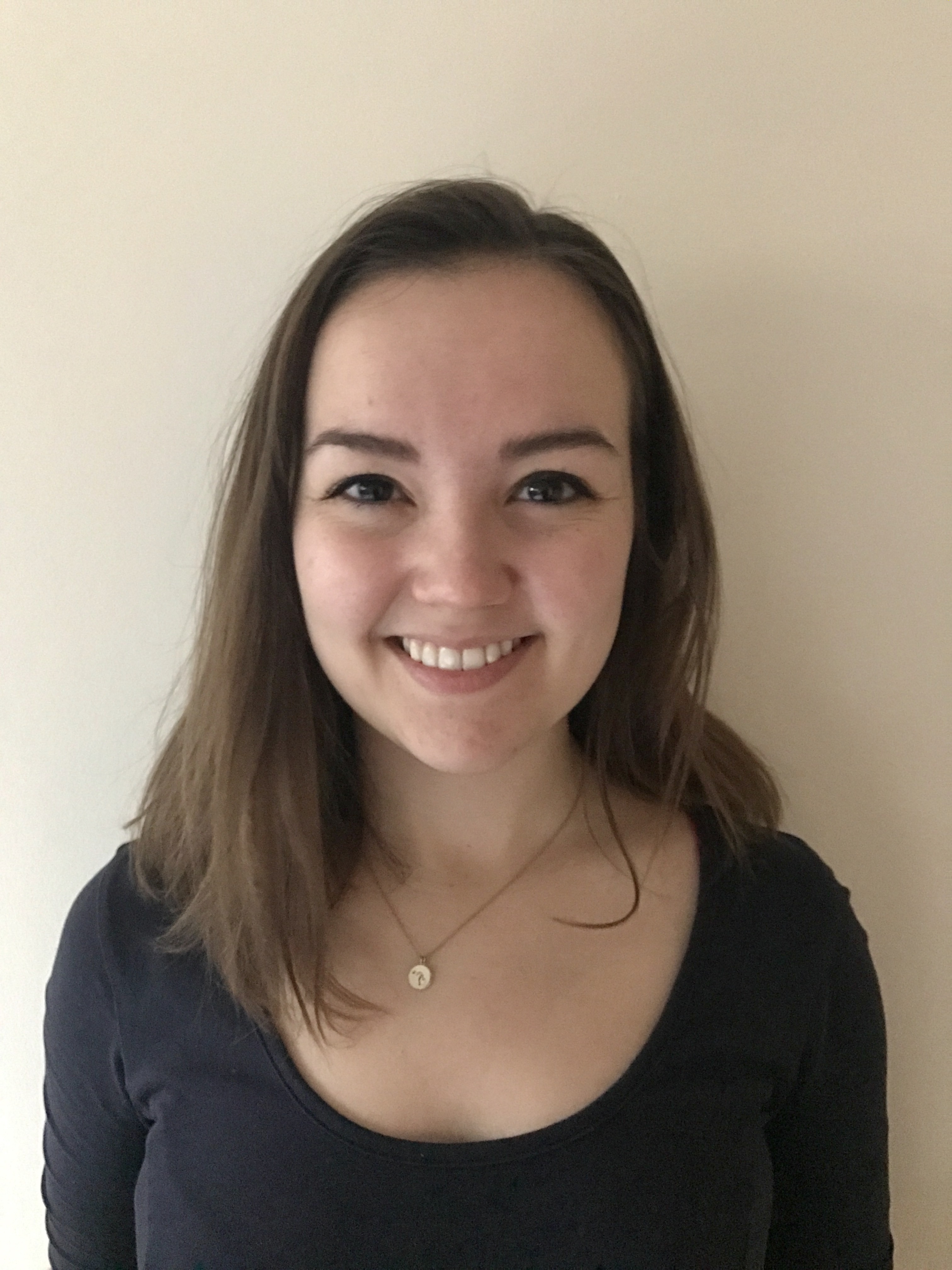

Anna Forringer-Beal on investigating ways to reposition trafficking as a human rights concern rather than a criminal issue.

Gates Cambridge’s emphasis on leadership by bringing others up with you is what motivated me to apply and compels me to return.

Anna Forringer-Beal

While she was at high school Anna Forringer-Beal [2019] worked as a research assistant on a university project about people who risked their lives making the dangerous crossing from Mexico and Central America to the US.

Her research work involved building a catalogue of artefacts that researchers had collected on the borders of Mexico and Arizona. Anna recalls finding a really tiny shoe – a trainer with velcro straps. Friends of the child who had owned it had written messages on the shoe such as ‘we’ll miss you’ and ‘we wish you well’. “It was heartbreaking, especially knowing where that kid must have ended up. It shaped me profoundly,” says Anna. “It made me realise I was in a position of power and that I should not be working in this space unless I was trying to dismantle violent systems and help others.”

Anna is about to begin a PhD at the Multidisciplinary Centre for Gender Studies which builds on her master’s at the same centre. For both she received a Gates Cambridge Scholarship.

For her PhD she will compare the Modern Slavery Act with the US’ Trafficking Victims Protection Act. She wants to go back to the roots of the acts and look at ways to reposition trafficking as a human rights concern rather than a criminal issue. That would mean emphasising victim support and resources over punitive measures. She feels this is the best way of reducing trafficking.

While popular discussions of trafficking readily paint victims with broad strokes, their experiences vary greatly. Anna says that it is important to recognise the different social identities trafficking victims have because it affects the process by which they could leave a trafficking situation. For example, because of immigration legislation, many trafficking victims who are also undocumented are afraid to come forward for fear of being deported. “The best tool traffickers have is a restrictive immigration system. It’s their best friend. They tell victims that they will be kicked out of the country if they report the abuse – and the government’s treatment of immigrants backs this up. We need to break that loop,” says Anna. “We have the resources to care for victims and if it cuts down on a crime as heinous as trafficking then we should do it.”

She adds that current anti-trafficking legislation is very similar to that used nearly a century ago. It is based on the idea that trafficking is committed externally when much trafficking now happens within the US and UK. “It’s based on an old-fashioned mindset. We should be open to trying something different,” she says.

Early research

Anna, who was born in Michigan, started doing academic research early. At 16, she joined The Undocumented Migration Project as a research assistant at the University of Michigan as a result of a unique internship programme at her high school. That involved interviewing undocumented immigrants, many of whom had faced violence during the crossing into the US. This was to form the basis of her undergraduate thesis.

Although she was focused on anthropology, archaeology and sociology from an early age while pouring over National Geographic and archaeology magazines, Anna says gender has always been a major theme running through her life. Early experience of witnessing the impact of an abusive relationship on her mother made her more attuned to the pressure to conform to traditional gender roles. “Seeing my mother try to carve out a sense of self had a big impact,” she says, adding that she was drawn to understanding family structures and culture – “what makes people who they are”.

As an undergraduate at the University of Michigan Anna says she sought out the opportunity to work in the university’s sexual assault prevention and awareness centre. At the centre, where she was a coordinator, she managed 44 volunteers and taught over 500 freshmen about sexual consent. It helped her to process the unhealthy relationship between her parents and gave her valuable teaching experience. Indeed she created the syllabus for a mini undergraduate course on gender violence in the history of the feminist movement.

With one foot in activism and the other in academia, Anna approached her undergraduate thesis with an eye to gendered differences during the migration process. While her previous research focused on the archaeological record of migration, her thesis employed ethnographic techniques to reveal what the artefacts could not.

Anna had noticed that there were few demonstrably female clothes in the records compared to the number of women crossing the border reported by American border patrol. By speaking with women preparing to cross in Chiapas, Mexico, she hoped to find an answer to this discrepancy. She thought many of the women might be wearing masculine-style clothing to de-emphasise their gender, but she found instead that many were playing up their femininity. Women would apply make-up and select jewellery in order to better blend in with the non-immigrant population. They were also strategic in the partners they travelled with or linked up with other migrants along the way. “They were using femininity as a tool to make the crossing safer for them,” says Anna. “This flew in the face of previous research suggesting women were merely victims. They knew what they were doing: they were being strategic.”

From activism to a PhD

Anna turned once again to activism on graduating from university. She worked for the nonprofit, Polaris, on their national human trafficking hotline. It was a chance to have a direct impact. The work was a mix of everything she had been doing previously, for instance, many of those trafficked were immigrants and many others had been in abusive relationships. She realised that, despite the span of people affected by human trafficking, there were some common themes. Unfortunately, one was the ineffectiveness of policy. So although she loved the work, she realised that she was not dealing with the source of the problem: policy and law enforcement.

After a year of working on the hotline, she started her master’s in Multi-disciplinary Gender Studies at Cambridge with the support of a Gates Cambridge Scholarship. She was drawn to the Centre for Gender Studies at Cambridge because it allowed for a multidisciplinary approach that was used for her master’s. For her research, Anna studied how the White Slave Panics of the early 20th century influenced contemporary anti-trafficking policy. Specifically, she investigated the UK’s Modern Slavery Act and, drawing on her ethnographic background, spoke to MPs about their approach to policy-making. By drawing a connection between the historical anti-trafficking methods and modern policy responses, Anna was able to demonstrate the similarities between the two – suggesting the need for a new, human rights-focused approach. Her PhD will pick up where her master’s left off by expanding this conversation to US law in comparison to the Modern Slavery Act. While at Cambridge she has also been active in moves to open the curriculum as lead organiser of the University of Cambridge Gender Studies Decolonise Reading Group.

Since finishing her master’s, Anna has been working as a policy director in Michigan State Government. She is looking forward to returning to Cambridge in the autumn and reconnecting with the Gates Cambridge community. “I am beyond excited to rejoin the Gates Cambridge community. I have made the closest friendships within it in terms of both research and life. Gates Cambridge’s emphasis on leadership by bringing others up with you is what motivated me to apply and compels me to return.”

Anna Forringer-Beal

- Alumni

- United States

- 2017 MPhil Multi-Disciplinary Gender Studies

2019 PhD Multi-disciplinary Gender Studies - Darwin College

After seeing firsthand how the law impacted the daily lives of women through the Undocumented Migration Project or on the National Human Trafficking Hotline, I felt compelled to study the construction of laws and the cultural attitudes which influence them. Through an MPhil in Gender Studies at Cambridge, I was able to explore how stereotypes about immigrants and sex workers impacted data gathering, victim assistance, and ultimately limited the scope of the UK Modern Slavery Act of 2015. I am humbled to be returning to the Gates Scholar’s Community to expand this project through a PhD in Gender Studies. By constructing a genealogy of anti-trafficking law stretching back to the White Slave Panics of the late 1800’s, I aim to show that anti-trafficking laws are currently constrained by xenophobic thought. It is my hope that this work will refocus anti-trafficking policy to human rights and survivor support as the most effective tools in combating trafficking. When not writing about human trafficking, I can be found baking, boxing, or fastidiously reorganizing my to-do lists.

Previous Education

University of Cambridge MPhil Gender Studies 2018

University of Michigan Bachelor of Arts Anthropology 2016