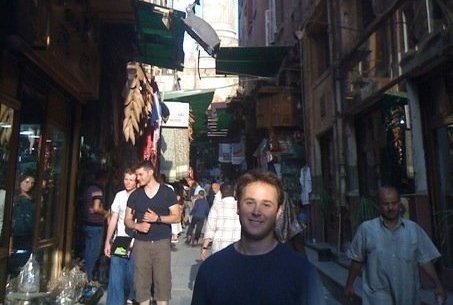

Max Reibman talks about his research into the recent history of the Middle East.

Studying the history of political upheaval in the Middle East in Cairo just months after the Tahrir Square revolution certainly puts history in perspective.

Max Reibman [2010] travelled to Egypt in the second year of his PhD, and as a historian studying the 1919 revolution he was able to experience the latest, powerful manifestation of the country’s long history of social protest and change.

“I strongly believe that charting political instability in the region on a daily basis is not as useful as an approach which looks at the stresses and conflicts with a longer view,” he says. He is optimistic about developments in Egypt despite all that has happened since the Tahrir Square demonstrations.

“I think the country has changed for the better. The government now has to be conscious of the ability of people to mobilise. Individuals today are far more politically savvy and social activism has been a key component of this,” he says.

Political debate

Max’s interest in politics and history began at an early age. Born in New York City, Max attributes his academic interest in history, languages and foreign travel to his parents. His father has a Master’s degree in Russian history and his mother is a Francophile. Family events were full of intense debates about the British Empire, US politics and global affairs.

Holidays were spent at civil war battlefields, visiting museums, and touring Europe, including the beaches of the Normandy landings. In elementary school, Max attended after-school lessons in French which led to an interest in other languages, cultures and global events in general.

At the University of Pennsylvania where Max graduated summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa, he majored in history and minored in cinema studies. He also began his study of Arabic driven by an interest in the history of the British Empire, particularly its policies in the Middle East, and was encouraged by a number of his friends who were from the region.

One of his professors at Penn had been a fellow at Trinity College, Cambridge, and he encouraged Max to take part in a summer fellowship programme linking the University of Pennsylvania with Pembroke College. “It exposed me to the uniqueness of Cambridge,” he says. He met teaching and administrative staff who had essentially played a role in the last days of the British Empire in the Middle East. Pembroke College was also home to the papers of the former governor of Jerusalem.

“Being there was an inspiration,” says Max. “It was such a rich community of intellectuals and people dedicated to their subjects, people who really excelled as diplomats and historians. It is difficult to appreciate how special that community is and how available that richness is to students,” he says.

King-Crane Commission

He applied for an MPhil at the University and received a fellowship from the Faculty of History. He had no intention at the time of staying on for a PhD, but he really enjoyed the intellectual atmosphere and says his supervisor, Dr Tim Harper, was a key mentor to him.

For his MPhil he developed his senior undergraduate thesis on the creation of the British mandate in Palestine and the period immediately following the First World War in the Middle East. His focus was on the King-Crane Commission, an official investigation by the United States government concerning the disposition of non-Turkish areas within the former Ottoman Empire.

The commission toured the Middle East and was the first formal such investigation by the US. For Max, it is clear evidence that the US had economic and political interests in the Middle East far sooner than historians sometimes think. “Things in the region at the end of the First World War were very uncertain. There were arguments about a greater Syrian state and a greater Lebanon and discussions about uniting Syria and Egypt,” he says.

He also studied the Peel Commission, the last effort by the British to ease the situation in Palestine through a diplomatic solution. “There’s an assumption that the UK’s mandate was inevitable, but nothing was inevitable,” says Max.

Egypt

He applied for a Gates Cambridge Scholarship for his PhD, planning to extend the scope of his MPhil work and aimed to focus most of his research on Egypt which was key to developments in the region at the time. The centre of Arab nationalist movements, Egypt had a vibrant exile community from across the Middle East and important newspaper and journals. Moreover, a number of US diplomats used Cairo as a hub to explore the region.

“Egypt is often seen as being home to an interesting mix of cultures, but equally important were the political movements which came together there to challenge the European colonial powers,” says Max.

“Cairo emerged in the First World War and its aftermath as a major international political centre”.

Fluent in both French and Egyptian Arabic, Max spent a year in Egypt doing fieldwork and says that experience was vital to understanding how events unfolded in real time. It also allowed him to add a crucial oral historical component to his research from talking to people who shed light on the events of the past.

For his fieldwork, Max was based in the Egyptian National Archives, a Nasser-era building overlooking the island of Zamalek in downtown Cairo. Amid protests and demonstrations, the archive periodically closed early or was shut down entirely. The head of the archive was later replaced at one point by a political appointee of the Muslim Brotherhood, showing how the study of history remains highly politicised and contentious in the country.

His research has led Max to publish for the Carnegie Endowment think tank in Washington, DC, and he has been quoted in the regional press on a number of occasions.

Global risk

He currently works for the Risk Advisory Group in Dubai. Headquartered in London, the Risk Advisory Group is a global risk management consultancy that helps some of the world’s largest companies navigate the business and political landscapes of complex markets.

Max says he routinely uses his skills as a historian to create compelling narratives about the risks associated with operating in complicated jurisdictions or working with certain partners. He is also able to exploit his solid network of contacts across the Middle East to undertake due diligence work.

In the future, Max plans to eventually publish his PhD as a popular history book. “There is so much interest in the Middle East and I think my research would make a positive contribution to ongoing debates,” he says, adding: “What I enjoy most is writing about ordinary individuals who have largely been forgotten by history, but who were at one point important actors in creating the modern Middle East. I want to bring them to life again and to show that their stories still resonate today.”